Bud & Arnie

Bud and Arnie, by Elaine Tooley

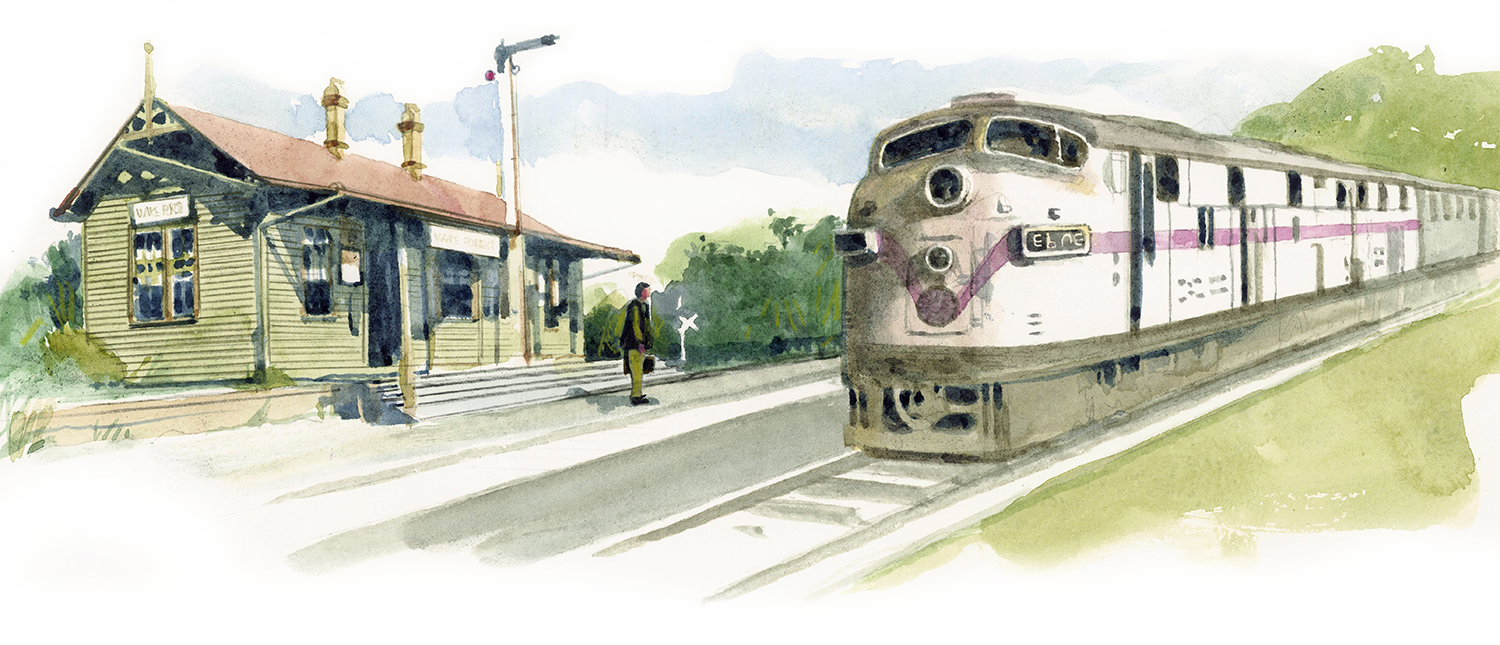

The two were almost inseparable. If you saw one, you were certain to find the other close by. So it was only natural that they boarded the streamliner train together. With a final whistle, the engine left Wake Forest headed toward Cabin John, Maryland, just down the Potomac from Washington, D.C.

The two were almost inseparable. If you saw one, you were certain to find the other close by. So it was only natural that they boarded the streamliner train together. With a final whistle, the engine left Wake Forest headed toward Cabin John, Maryland, just down the Potomac from Washington, D.C.

Classmates stood on the platform to see them off, some planning to join them later. For now, though, this trip was like so many other times before — just the two of them. The friends, the hum of the rails and their memories for 250 miles.

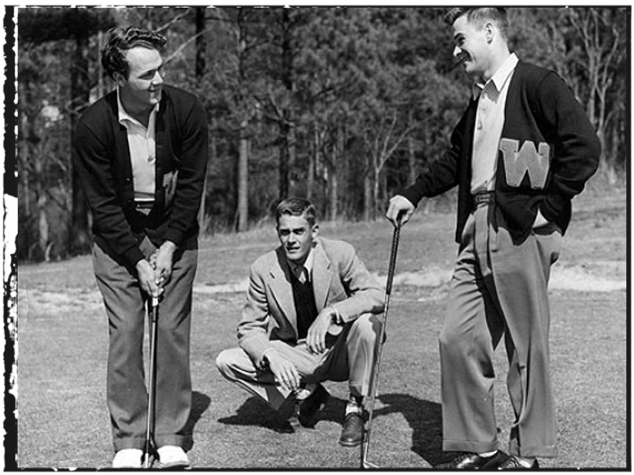

Bud Worsham and Arnold Palmer (standing)

with fellow competitors at a Hearst National

Junior Golf Championship.

Late in the summer of 1946, Detroit hosted the Hearst National Junior Golf Championship. At 16 years old, and a student at Latrobe High School in Pennsylvania, Arnold Palmer (’51, LLD ’70) entered the tournament and played so well that the news made quick work getting back to his hometown.

Late in the summer of 1946, Detroit hosted the Hearst National Junior Golf Championship. At 16 years old, and a student at Latrobe High School in Pennsylvania, Arnold Palmer (’51, LLD ’70) entered the tournament and played so well that the news made quick work getting back to his hometown.

“Latrobe Is Proud of Arnold Palmer,” read the headline in the Latrobe Bulletin the night before the title match. A day later, Latrobe’s boy walked away as the runner-up, not yet the king.

Many point to this event as a key marker in Palmer’s life. It was his first time on the national stage, and he delivered a solid performance, foreshadowing glimpses of greatness that would last for decades. But it wasn’t the exposure or the near-victory that Palmer recalls about that tournament. Something else happened.

“Something that would have a far greater impact on my career and life than winning,” Palmer confessed. “I met Buddy Worsham.”

Marvin Worsham was the youngest of Lewis “Buck” and Irene’s five children. Their four boys all played golf, but rumors swirled that the youngest had it in him to be the best of the brothers. That was saying something, given that Lew, the oldest, beat Sam Snead to win the first televised U.S. Open Championship in 1947.

Marvin Worsham was the youngest of Lewis “Buck” and Irene’s five children. Their four boys all played golf, but rumors swirled that the youngest had it in him to be the best of the brothers. That was saying something, given that Lew, the oldest, beat Sam Snead to win the first televised U.S. Open Championship in 1947.

When the two teens met, Arnold wasn’t fond of the Worsham family’s nickname for Marvin.

“His family called him ‘Bubby,’ a nickname that didn’t suit him, in my mind,” Palmer explained. “I called him ‘Bud’ from day one — it simply seemed to suit him better.”

From then on, Marvin was Bud. And Arnold was Arnie.

Like any two teenagers, Bud and Arnie joked around, pulled pranks and ate as if their stomachs had no bottoms. They golfed and laughed and golfed some more. They were friends.

On the course, the athletes were similar in their success, but drastically different in how they achieved it. Arnie’s swing followed his general philosophy: Hit it hard. Bud, on the other hand, was forced to find a more creative approach.

When he was 6 years old, Bud, his brother and two friends were playing at a neighbor’s house. The neighbor was operating his tractor, attempting to plow down some overgrown broom sage, when — because of boyhood horsing around — Bud’s right leg got caught in the machinery. Even after months of physical therapy, Bud was left with a considerable limp. In order to play the game he loved, he figured out a way to swing a club and drive the ball by putting all his weight on one leg.

“He could hit it a mile that way,” Palmer remembered.

After that first meeting, Bud and Arnie went their separate ways until golf called them back together.

The next summer, Bud, a four-year team captain, was coming off of two undefeated seasons and back-to-back golf titles for Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School. He also claimed victory at the greater Washington, D.C., area’s first District Junior Open.

The next summer, Bud, a four-year team captain, was coming off of two undefeated seasons and back-to-back golf titles for Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School. He also claimed victory at the greater Washington, D.C., area’s first District Junior Open.

Arnie had a good showing himself during his final high school season playing for the Latrobe Wildcats. His amateur championships were stacking up; he was earning titles across Pennsylvania and the nation; and by the time he received his high school diploma, he was ranked the No. 2 amateur golfer in the United States.

The Hearst National Junior Championship selected Los Angeles as its host city that year, so the two teens boarded a train headed west. Golf clubs in tow and eyes on victory, they jabbered the 2,500 miles over the Appalachians, across the Mississippi and through the Mojave.

“Bud talked up a storm about where he was going to college,” remembered Palmer. “Some place down south called Wake Forest.”

In 1933, Wake Forest had started fielding a golf team, but it was informal. There was no official coach; there was no actual recruiting. Golf was more of a pastime for students who were already on campus and enjoyed the game. So lackadaisical was the approach that the athletic director, Jim Weaver, told of the time in Georgia when a tournament director, short on help, asked the Wake Forest boys to give up playing in order to serve as caddies.

The ultracompetitive Weaver decided it was time to become a force in the Southern Conference, the precursor to the Atlantic Coast Conference, and tapped Clement “Johnny” Johnston (’47), an Army Air Force veteran, to serve as a part-time player-coach. Soon the two began intentionally recruiting players who had proven success and burgeoning potential.

First on their list was an impressive young player from the D.C. area with the talent and gumption to help build a competitive NCAA team. Weaver, wanting him on the links for the Deacons, offered Wake Forest’s first-ever golf scholarship to Bud Worsham.

Because of his golf talent, Bud was the first in his family to attend college. In addition to the tuition, room, board and book costs, there was one feature the new college-bound man appreciated above all.

“Down there,” Bud said, “you could play golf all winter long!”

The thought was too good to be true for Arnie, forced to abandon the game for months because of Northern weather. But Arnie didn’t have plans like Bud. All he knew for sure was he wanted to play golf.

Arnie and his dad had talked about college, but the money wasn’t there. Penn State and Pittsburgh expressed interest but could only offer partial scholarships. His best plan was to stay in Latrobe, work at the country club and take business courses at nearby St. Vincent College.

By the time the teens arrived in Los Angeles, they were ready to showcase their talent, but from the beginning, their performances lacked luster.

“We both lost in the first round,” explained Palmer. “But the tournament sent the losers to Catalina Island.”

So Bud and Arnie ferried over to enjoy their consolation prize.

“We were playing poker and hitting golf balls out the hotel window,” described Palmer in a 2015 interview. “Bud says to me, ‘Arn, where are you going to college?’ I told him I didn’t know.”

Taking on the role of recruiter, Bud was relentless in his efforts. “Arn, you’ve got to go to Wake Forest. You’ve just got to go to Wake Forest, Arn!”

“Bud’s idea was that he could convince Jim Weaver to give me a similar deal,” Palmer revealed. “Bud called Weaver from California, and I called my mother and asked her to send my high school transcripts to Wake Forest, a place I knew nothing about except it was somewhere in North Carolina and sounded like heaven.”

On that call between Bud and Weaver, the athletic director asked one question: “Can he play golf?”

When Arnie arrived home, there was a letter with the same scholarship offer as Bud’s. Wake Forest had its first two golf recruits.

Entrusting his future to Bud’s persuasion and Weaver’s scholarship wizardry, Arnie waved goodbye to his family and the hometown that loved him and boarded a bus south. The 425-mile journey through the hot summer night left him with a neckache, bleary eyes and a sticky brow, but when the wheels finally stopped, Arnie found himself in the small, bustling village of Wake Forest. Down the steps he clambered with his suitcase and golf bag, yet without the faintest idea of where he was or where to go.

Entrusting his future to Bud’s persuasion and Weaver’s scholarship wizardry, Arnie waved goodbye to his family and the hometown that loved him and boarded a bus south. The 425-mile journey through the hot summer night left him with a neckache, bleary eyes and a sticky brow, but when the wheels finally stopped, Arnie found himself in the small, bustling village of Wake Forest. Down the steps he clambered with his suitcase and golf bag, yet without the faintest idea of where he was or where to go.

On one side of the road, he spotted shoppers milling about storefronts and passing movie theaters. On the other, he caught sight of what must have been the college he’d blindly committed to. Meandering along paths, passing brick buildings and magnolia trees, he found Gore Gymnasium, where he followed the sound of voices. He approached a doorway and lingered outside, not quite willing to interrupt the two men in conversation. Noticing the loiterer, the voices quieted, and a deep Southern drawl asked the young man what he wanted.

Arnie said he was looking for Jim Weaver. After taking in the 5 feet, 11 inches, with sturdy shoulders and strong arms, the two men swapped curious looks.

“Who are you?” the Southern drawl inquired.

“Arnold Palmer.”

“Well, Mr. Palmer,” said Weaver in his charming accent as he extended his hand, “welcome to Wake Forest.”

Weaver introduced the newcomer to the other man in the room — Douglas “Peahead” Walker, Wake Forest’s football coach. Arnie had played football back in Latrobe, and throughout his college years, the coach never missed an opportunity to recruit the golfer to play a few snaps. Walker even sent Harry Dowda (’49) to try his persuasion on the newbie.

“Arnold, come play football with us,” Dowda encouraged. “There’s no future in golf.”

Alas, even the World War II hero who would go on to play for the Washington Redskins and Philadelphia Eagles could not talk Palmer onto the gridiron.

After the introductions, Weaver went to work melding the returning golfers with new recruits.

“With the arrival of some outstanding new golf talent, Deacon hopes for a successful links campaign have gone on the upsurge,” reported the student newspaper, the Old Gold & Black.

The 1948 Howler yearbook read more like a hopeful, yet restrained, fortune cookie: “Prospects point toward a favorable season.”

Bud and Arnie settled into life at Wake Forest — swapping time between classes, social life and golf. In many ways, they had much in common; but just as their swings were drastically different, these two friends also found that where one was weak, the other was strong.

“Socially and academically, Bud and I had a system of sorts worked out where we more or less looked after each other,” explained Palmer. “Our strengths and weaknesses beautifully complemented each other’s. I had a stronger physical constitution. ... Bud was shyer than me, so it was left to me to speak to girls. ... On the academic front, Bud had a strong work ethic and was forever on my case about keeping up my grade point average to avoid losing my scholarship and being put on academic probation or, worse, getting kicked out of school.”

Bud had something of a challenge on his hands. More than once, Arnie was asked to pay a visit to the dean’s office for “friendly chats about his casual academic performance.” But Bud’s constant cajoling and encouragement kept Arnie in the books and on the course. And it wasn’t long before Wake Forest realized what it had in these two.

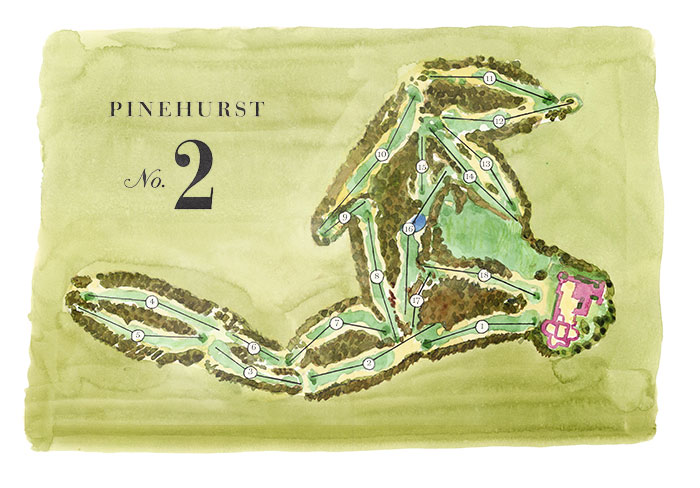

At the end of Bud and Arnie’s first collegiate golf season, the Wake Forest golfers stood at Pinehurst Course No. 2, vying for the Southern Conference Championship against eight other teams and noteworthy talent. The team had wrapped a remarkable 13-match season, losing only once in a squeaker to North Carolina State; besting University of North Carolina and its ace, Harvie Ward, who was considered the best collegiate golfer in the South; and claiming victory over Duke’s Art Wall and Jim McNair on their own course, a feat that hadn’t been accomplished by any competitor in more than a decade.

At the end of Bud and Arnie’s first collegiate golf season, the Wake Forest golfers stood at Pinehurst Course No. 2, vying for the Southern Conference Championship against eight other teams and noteworthy talent. The team had wrapped a remarkable 13-match season, losing only once in a squeaker to North Carolina State; besting University of North Carolina and its ace, Harvie Ward, who was considered the best collegiate golfer in the South; and claiming victory over Duke’s Art Wall and Jim McNair on their own course, a feat that hadn’t been accomplished by any competitor in more than a decade.

Upperclassmen Raymond “Sonny” Harris (’50) and Jennings Agner (’52) rounded out the Wake Forest foursome that included the two 19-year-olds, Bud and Arnie. They leaned on their clubs, knowing what was riding on each stroke: Weaver’s dream of leaving Wake Forest’s “pushover” reputation behind; immense school and community pride; and a potential grandiose finish to the first year the golf team made a move toward serious competition.

The golfers swung, the audience cheered, and Weaver, with a mix of excitement, anticipation and pure nerves, paced a well-worn path. At the end of 36 holes — for which Bud registered a 152 and Arnie shot a 145, 1 over par — the aggregate scores were 12 strokes off the Blue Devils, and Duke took the top spot that day. Wake Forest placed second. When the individual results were posted, Arnie had claimed the title by a stroke.

“This is the Wake Forest golf team that will go down in the annals of Deacon athletics as one of the best teams ever to represent the Baptists,” reported the Old Gold & Black. “Arnold Palmer won the individual honors at Southern Pines and is now king in this league.”

To Weaver’s pleasure, the two recruits’ first season and subsequent almost-championship was a statement to the collegiate athletic world that Wake Forest was playing to win.

Growing up with a golf pro for a father, there was barely a chore related to golf courses that Arnie hadn’t done. Bud had the same-yet-different kind of know-how, mostly from his caddying days reading the greens for Del Webb, the real estate entrepreneur and co-owner of the New York Yankees.

Growing up with a golf pro for a father, there was barely a chore related to golf courses that Arnie hadn’t done. Bud had the same-yet-different kind of know-how, mostly from his caddying days reading the greens for Del Webb, the real estate entrepreneur and co-owner of the New York Yankees.

After their first season surpassed all expectations, Bud and Arnie gathered a few teammates on the practice greens during a “lull in studies.”

“Using wheelbarrows and shovels ... we built the college’s first grass greens, replacing the modest nine-hole course’s original sand greens with something that at least resembled a competitive putting surface,” stated Palmer. “As I recall, the athletic department paid us 50 cents an hour for our efforts, and we were very proud of our handiwork.”

The new greens inspired the team to play more often and with greater precision, increasing their ability and reputation as true contenders. Like in their first season, the number one and two spots were carried by Arnie and Bud, respectively. Agner and Harris returned to the core four, and several newcomers added talent to the team.

The team’s schedule was littered with stiff competition the second time around. Even so, the team lost only two matches. At the Southern Conference title match, where they were considered favorites, the Deacons lost by a stroke to the Blue Devils. Arnie defended his individual title, becoming the Southern Conference Champion for the second time in two years. Their strong showing also won them a bid to the NCAA tournament in Ames, Iowa, where playing through absurd heat and tree-trembling thunderstorms, Arnie, “who only showed disrespect for par,” took medalist honors in the qualifying round.

Arnold Palmer, Coach Johnny Johnston and Bud Worsham

Visitors were frequent at the Worsham home — a 1920s Sears Roebuck kit house with a large front porch. Arnie, a guest of Bud’s on school breaks or long weekends, dropped by enough to be a pseudo sixth child.

Visitors were frequent at the Worsham home — a 1920s Sears Roebuck kit house with a large front porch. Arnie, a guest of Bud’s on school breaks or long weekends, dropped by enough to be a pseudo sixth child.

On his visits, Arnie learned that Bud’s parents were raised on tobacco farms in Virginia, bookended large families and attended a one-room schoolhouse. Buck was a carpenter who helped build battleships for the U.S. Navy in World War I and later worked to restore Colonial Williamsburg. His neighbors called him “the hardest-working carpenter you ever knew,” and he proved it every day until he retired at age 82.

Irene’s expertise as a seamstress kept her family and neighbors clothed, while Buck’s garden was the envy of every citizen of Cabin John. At his hand came Belgian giant tomatoes, popular among the neighbors, and vegetables that Irene canned and placed beside her stockpile of canned chicken. Anyone who stopped by the Worsham home left with a jar of homemade honey.

When the college boys were in town, Irene served her famous fried chicken. They visited the golf courses the Worsham brothers frequented, and if they were lucky, Bud’s sister would make them cookies for the drive back to Wake Forest.

During their visits farther north to Latrobe, the boys stopped by the country club where Arnie’s dad was the head golf pro. They’d play the “short, but imaginative” nine holes that Deacon Palmer had built with his own hands when he was a teenager.

While the boys and their families saw one another at tournaments across the country, the visits to each other’s homes solidified the bond. They knew one another’s parents, siblings and all the stories that made for perfect teasing fodder.

“My junior year at Wake Forest was, in retrospect, maybe the most fun of all my college years,” Palmer said. “There were lots of laughs and more competitive golf than I suppose I’d ever played in my life. Bud and I grew socially more confident but were still basically inseparable.”

If the golf was fun to play, it was just as fun to follow.

“Prospects are the best this season they have ever been for a truly great golf team,” read the Old Gold & Black in the spring of 1950. “This year, the team members are gunning for the title. ... Palmer is recognized as one of the best amateur golfers in the United States. ... Bud Worsham and Sonny Harris seem to have the inside track in retaining their places on the squad.”

Arnie had already knocked in three holes-in-one for the Deacs; his 18-hole averages were in the high 60s and low 70s; and he only went over par one time. So far, in his 30-match career at Wake Forest, he had carded a single loss.

“Worsham, the number two man on the squad for the past two years, teams up with Palmer to give the Deacs a potent one-two punch,” wrote Wiley Warren (’52), a sports columnist for the Old Gold & Black. “He is not too large, but hits an extremely long drive, and he is especially deadly with a putter. He tied the Carolina Country Club course record with a sizzling 64 this year,” a stat he shared with his best friend.

“Bud is probably one of the most underrated athletes at Wake Forest,” declared another budding Wake Forest journalist. “He has been somewhat overshadowed by the great golfing exploits of his best friend. ... One of the better amateur golfers in the country, Bud has won many tournaments to prove this fact. ... He began his golfing career as a caddy and ... has become quite apt at chasing the little white pellet around the links.”

The rest of the squad was made up of Sonny Harris, a law student and World War II veteran who was “a sure, steady player and a long, hard driver”; George “Dick” Tiddy (’53), a 6-foot-6-inch, 255-pound giant who went by “Big Train”; Michael “Mickey” Gallagher (’55), known as “Thin Man,” who was rarely rattled and served as an excellent recover-shot artist; Frank Edens (’53), who liked to hunt when not golfing; and Jim Flick (’52), a conservative player who “seldom tries reckless shots.”

With strength, depth and talent, the Wake Forest boys were making a name for themselves, and to the envy of many and the sheer delight of Weaver, frequently rated in the top three teams in the nation.

“Coach Johnston’s only trouble so far seems to be the fact that he is blessed with too many good men,” wrote Warren. “All are capable of giving par a terrible licking on any given day.”

That third season, the team went 13-1, losing only to the Tar Heels. Wake Forest’s top four — Arnie, Bud, Big Train and Thin Man — took the Southern Conference title played at the Old Town Club in Winston-Salem and set a new conference record by five strokes. Their monumental season continued as they headed to the NCAA tournament in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

“As far as he is concerned, Marvin (Bud) Worsham of Wake Forest golfing fame says that he would like nothing more than to see the Deacon golfers win the NCAA tournament,” reported the Old Gold & Black before the athletes headed west.

Bud’s wish didn’t come true, but the team finished fifth, Arnie was again a medalist, Big Train won the driving contest with a swing that sailed 340 yards, and Harris was the last Wake Forester to be eliminated, just failing to make it to the national finals.

“Worsham thinks this year’s edition of the Deacon links team is the greatest team he has ever played on,” wrote the Old Gold & Black. “When asked about his most thrilling experience on this year’s team, Bud will tell you it came when they captured the Southern Intercollegiate golf crown in Athens, Georgia.”

And perhaps the Southern Intercollegiate tournament was the most poignant moment of the season. Arnie won the individual title, carding 8 under par and beating his North Carolina nemesis, Harvie Ward, by two strokes. Arnie, Bud, Big Train and Thin Man were again the four on the course for the Deacons who proved that Wake Forest golfers had come a long way from serving as stand-in caddies to being standout champions.

In the fall of 1950, seniors Bud and Arnie congregated with the Groves Stadium crowd on homecoming afternoon when Wake Forest faced the George Washington Colonials. Bud, with his wide smile and good humor, spent the first half of the game selling programs for a little extra spending money. By the second half, he was in the stands watching Guido Scarton (’52) score the first touchdown and cheering when Larry Spencer (’54) cemented the shutout victory with an interception-turned-touchdown.

In the fall of 1950, seniors Bud and Arnie congregated with the Groves Stadium crowd on homecoming afternoon when Wake Forest faced the George Washington Colonials. Bud, with his wide smile and good humor, spent the first half of the game selling programs for a little extra spending money. By the second half, he was in the stands watching Guido Scarton (’52) score the first touchdown and cheering when Larry Spencer (’54) cemented the shutout victory with an interception-turned-touchdown.

Walking back to their rooms in Colonial Club, Bud and Arnie talked about plans for the evening. The Homecoming Dance was being held at the Armory in downtown Durham, and several hundred students, dressed in their best semiformal wear, would make the 20-some mile drive to dance to the sounds of Johnny Satterfield and his band.

Bud and Arnie planned to get dinner and go to the dance, but Arnie fell asleep. Soundly. Bud shook Arnie awake, telling him that he and Gene Scheer (’53), Jim Flick’s roommate next door, were headed to the dance in Durham. Bud asked his best friend to go along to help embolden him to talk to the girls who would be there.

The groggy, half-asleep Arnie declined, instead trying to persuade Bud to catch a movie with him and Jim. There was a double feature at Forest Theatre — Roy Rogers in “Bells of Coronado” and Robert Rockwell in “Unmasked.”

“Come on, Bud. Stay with me. Go with us to the movie.”

“No,” Bud said. “Gene and I are going to the dance.”

Neither would budge. In his book, “A Golfer's Life,” Arnie recalls falling back asleep, with plans to see Rogers and Rockwell. Bud and Gene left in their fancy clothes, Gene riding shotgun as Bud rambled his 1938 Buick sedan down Durham Road toward the big dance.

It had been less than 48 hours, but the words were a haunting echo now. The dance was over, Sunday had passed, and it was Monday morning. With the two men on the train, the final whistle blew and the engine roared away from Wake Forest.

Arnie sat on the train, the seat next to him empty. He stared out the window, bleary eyes affixed nowhere, combing through his memories as the scenery rushed by. Every now and then, he’d get up the courage to sneak a glimpse at the reality he so desperately wanted to be a bad dream. Near him, the casket was secure.

Bud didn’t stay.

After the movies, Arnie and Jim returned to Colonial House. Neither was able to stay awake waiting for the stories that Bud and Gene would bring back from the dance, so they surrendered to sleep, knowing they’d hear the details in the morning.

After the movies, Arnie and Jim returned to Colonial House. Neither was able to stay awake waiting for the stories that Bud and Gene would bring back from the dance, so they surrendered to sleep, knowing they’d hear the details in the morning.

When Arnie woke up, he noticed Bud’s bed hadn’t been slept in. The sheets were still neatly tucked around the mattress, and the pillow held no indentation from his head. Strange.

“It wasn’t like Bud to stay out all night — at least not without me along to take care of him,” thought Palmer.

Curiosity led Arnie down the hall. Several guys were jawing about the night before in Jim’s room, but neither Bud nor Gene was among them.

“I remember telling them to let me know if anybody heard from Bud or Gene,” said Palmer. “Then I went back to my room.”

An hour later, Jim knocked on Arnie’s door with a message: Coach Johnny Johnston wanted to see him. If the words hadn’t startled Arnie, the look on Jim’s face did. Something was terribly wrong.

“‘Arn, we’ve got a problem,’ Johnny told me somberly. ‘We think maybe Bud’s had an accident.’”

They piled into Johnny’s car and pointed it toward Durham, needing to find Bud and Gene. The road was hilly, bouncing up and down — much like the emotions and imaginations of the searchers.

“It was while we were riding in the car that Johnny broke the news to me that he thought Bud and Gene were dead,” recalled Palmer.

A few miles outside of Wake Forest, they passed evidence of a crash site.

Early that morning, on the part of the road where the bridge crossed over the Neuse River, Bud’s car was found near the river’s edge. According to the North Carolina State Highway Patrol, Bud’s car left the road, struck an embankment, hit the bridge abutment, flipped over and plunged 50 feet down, crashing and landing upside down in a rocky streambed, 5 feet from the water. The coroner guessed the accident happened around 1 a.m. on Sunday but wasn’t spotted until hours later when a neighbor noticed the wreckage.

“We drove to Durham in silence, searching for the funeral home where the authorities might have taken the bodies,” remembered Palmer.

They didn’t know exactly where to go. They made several stops before Johnny’s brother, a highway patrolman, learned the boys were taken to Raleigh. The car turned toward the capital.

Once they found the right place, the funeral director looked at Arnie.

“‘Who are you, family?’ he asked.”

“I told him I was Bud’s best friend,” Palmer said.

“Would you be prepared to identify the body?”

“I didn’t know what to say,” confessed Palmer. “I was numb with disbelief. I suppose part of me did wish to view the body — if only to prove that the nightmare was real.”

Arnie looked at the funeral director. “I guess so,” he whispered.

The funeral director led Arnie into a room.

“There they were,” Palmer said. “It was the worst thing I’d ever seen.”

After Arnie nodded his head to confirm that his best friend was dead, Johnny and Arnie left the funeral home, needing to find Bud’s car.

“Perhaps the shock was so great we needed to see the physical evidence of this unimaginable nightmare,” wondered Palmer, nearly 50 years after that day. “Or perhaps I wanted some other mental image to replace the one I’d just seen.”

At a junkyard outside of Raleigh, they found the sedan that had been the setting of so many good times. Road trips to Cabin John and Latrobe. Jaunts into Durham and Raleigh. Travels to the Carolina Country Club. Cruises down Faculty Drive and U.S. 1.

“It was crushed almost beyond recognition,” said Palmer, “but it was unmistakably the Buick.”

They didn’t know what to do next. What do you do when you realize your world will never be the same? When the idyllic life you had is seared in half? When you realize you will never talk to your best friend again?

Johnny took Arnie back to Colonial House to face his empty room.

“That was the last place I wanted to go, to tell the truth, but I couldn’t imagine where else to go,” Palmer said.

He called his parents, wishing the distance between them wasn’t so great.

“Their shock and grief almost matched mine,” he remembered. “They loved Bud like a son.”

That night, Jim Flick moved his stuff into Arnie’s room.

“I remember that we sat up late talking about what had happened, what we would do, and I don’t know what else,” Palmer recalled.

The following hours were a blur. The next morning, the campus community gathered in the college chapel for a memorial service. New president Harold Tribble was there; he hadn’t even been inaugurated yet. Dean D. B. Bryan, the one who helped Bud keep Arnie in class, attended. And the first person from Wake Forest that Bud or Arnie had ever talked to, Jim Weaver, spoke about Bud and Gene with a voice that must have belied its strength.

“To me, these boys typified the Wake Forest athlete,” Weaver said. “Neither was a Hercules, but they both had the courage of a David.”

“Shiny new heroes are turned out by mass production in every sport in the world today, but they don’t make them like Worsham and Scheer as often as needed,” classmate Wiley Warren wrote in his newspaper column. “You will remember the likable Worsham, with his short hair, muscular arms and wrists, and his quiet smile that seemed to always occupy his face.”

The editors of the Old Gold & Black also authored a tribute. “Most of all, we’ll miss them because they were such friendly, congenial boys, and when we think of them, it will be the little things about them that we will remember best — things like Bud’s smile that was always there. ...

This train ride was so different from the one the two friends took to California a few years earlier. On this trip, Bud wasn’t yammering on and on; he was silent. The only noise was an occasional quiet sob. In one more act of friendship, Arnie took Bud home to his family and final resting place.

This train ride was so different from the one the two friends took to California a few years earlier. On this trip, Bud wasn’t yammering on and on; he was silent. The only noise was an occasional quiet sob. In one more act of friendship, Arnie took Bud home to his family and final resting place.

“I had to take the body back to Washington, D.C., for the funeral,” shared Palmer. “It was the most horrible time of my life. I was just a kid, and I was hurting, and I felt like my world had come to an end. Sitting there in the baggage car of the train, looking at the coffin, crying, I decided one thing. If I ever got able, got the money, got the opportunity, I was going to do something to honor Buddy Worsham.”

After the devastating loss of his best friend, Wake Forest was not the same for Arnie.

“I thought I’d go crazy. I was always looking around for Bud,” he recalled. “Grief is one of the most powerful forces on earth, and almost always unpredictable. I’d never felt anything like the emotions and conflicting feelings suddenly turning over inside me. I wanted to play golf, but staying at Wake Forest suddenly felt empty and pointless without Bud there. I didn’t want to go to war, but I suddenly no longer wanted to be in college. I wanted to run away, but I wanted to be comforted. I wanted to sleep, but I wanted to wake up from this nightmare. Wake Forest without Bud was unthinkable.”

Palmer left Wake Forest and enlisted in the U.S. Coast Guard. For three years, he served his country. Rumors abound that Palmer swore off golf as he worked through his grief; in fact, the opposite was true. While everything in his life was shaken, golf remained constant, and he found his solace there.

Following his military service, Palmer returned to Wake Forest to finish his education. He golfed with new teammates, but without Bud there to keep him on track, Palmer skipped most afternoon classes to play the game that would change his life. With success looming, he left school with an ACC championship and a few credits short of finishing his business degree. You know the rest of the story.

Palmer was true to his word in that baggage car on the last train ride with his best friend. Throughout his life, Arnie honored Bud.