Who’s your buddy stories

Who's your buddy?

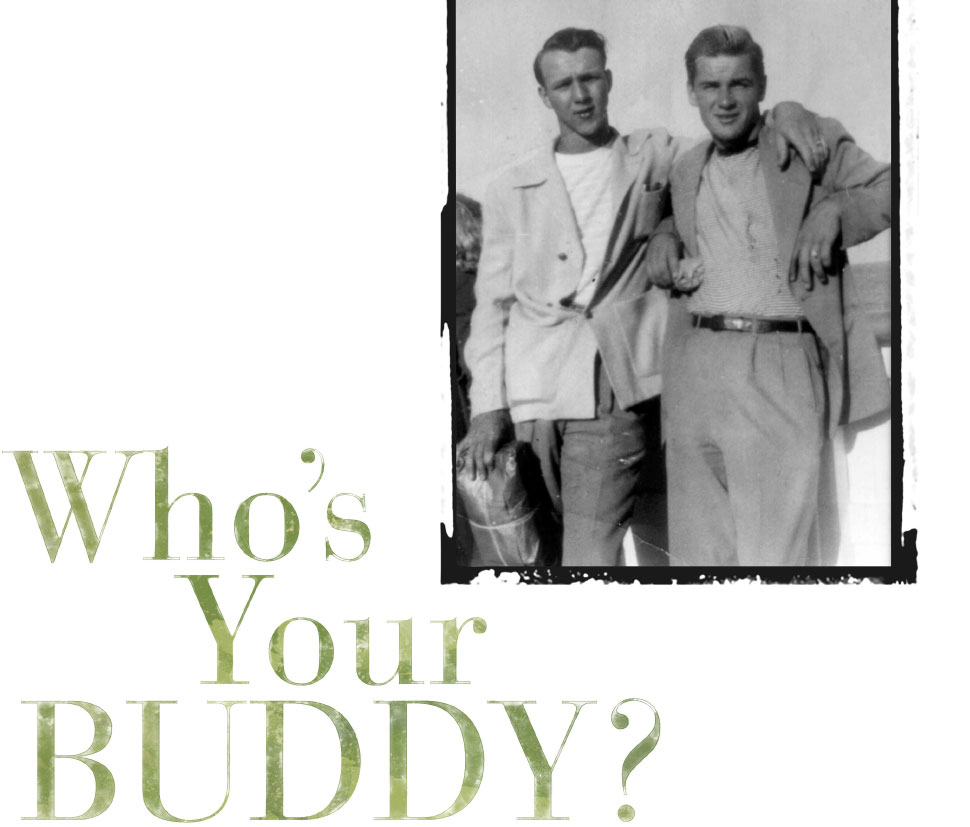

Marvin “Bud” Worsham (’51) &

Arnold Palmer (’51, LLD ’70)

The young golfer was making a name for himself as a four-year team captain, with two undefeated seasons and back-to-back high school state golf titles. He competed at national junior championships across the country, gaining success that caught the attention of coaches, colleges and competitors alike.

Wake Forest – who was seeking to shift from an informal program to a golfing force in the Southern Conference – was among those impressed by the young phenom. Thinking he had the talent and gumption to anchor the new program, Wake Forest offered their first-ever golf scholarship to a kid from the north.

His name was Marvin “Bud” Worsham (’51).

Just days before classes began in 1947, the young golfer asked if there was room on the team for one more. See, his best friend hadn’t made college plans yet.

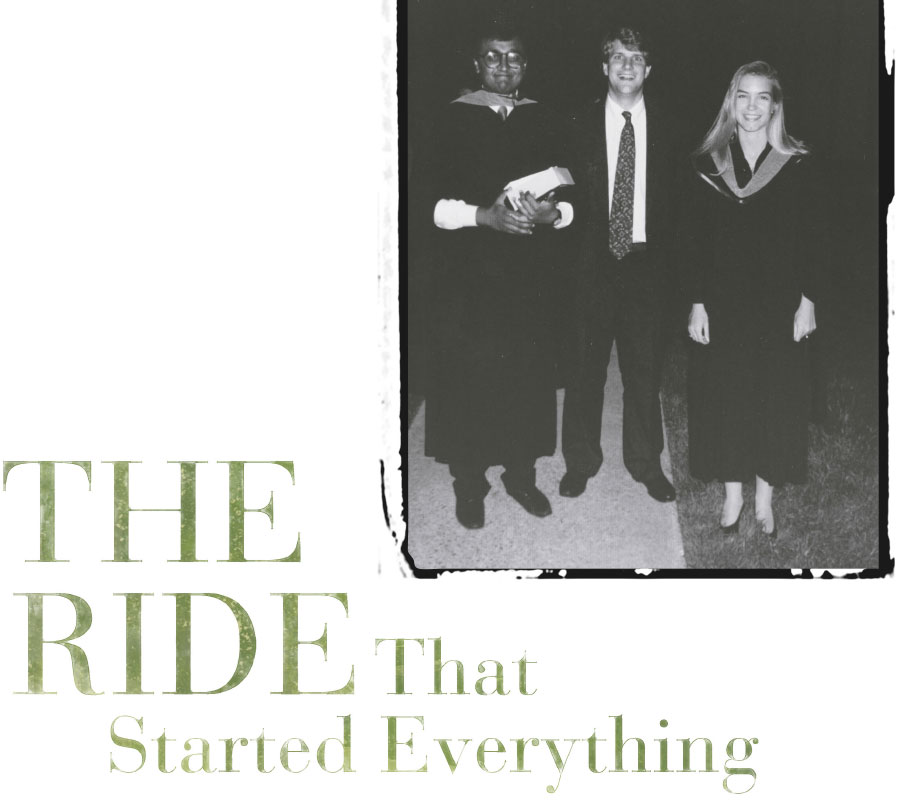

Bud Worsham and Arnold Palmer (standing) with fellow competitors at a Hearst National Junior Golf Championship.

“Can he play golf?” asked Wake Forest athletic director Jim Weaver.

“He’s better than I am,” replied the young man.

And so Wake Forest agreed to invite Bud’s friend to join the team.

His name was Arnold Palmer (’51, LLD ’70).

At just 16 years old, Palmer entered the Hearst National Junior Golf Championship in Detroit and walked away as runner-up. Many point to this event as a key marker in Palmer’s life. It was his first time on the national stage, and he delivered a solid performance foreshadowing glimpses of greatness that would last for decades. But it wasn’t the exposure or the near-victory that Palmer recalls about that tournament. Something else happened.

“Something that would have a far greater impact on my career and life than winning,” Palmer confessed. “I met Buddy Worsham.”

Marvin Worsham was the youngest of five children – four boys and a girl. All four boys played golf, but rumors swirled that the youngest had it in him to be the best of the brothers. That was saying something, given that Lew, the oldest, beat Sam Snead to win the first televised U.S. Open Championship in 1947.

When the two teens met, Arnold wasn’t fond of the Worsham family’s nickname for Marvin.

“His family called him ‘Bubby,’ a nickname that didn’t suit him, in my mind,” Palmer explained. “I called him ‘Bud’ from day one – it simply seemed to suit him better.”

From then on, Marvin was Bud. And Arnold was Arnie.

Like any two teenagers, Bud and Arnie joked around, pulled pranks and ate as if their stomachs had no bottoms. They golfed and laughed and golfed some more. They were friends.

After receiving Wake Forest’s first two golf scholarships, the two immediately got to work changing the reputation of the Deacon golf team. Their first season, the golf team tallied a 13-1 record and was runner-up at the Southern Conference Championship; Arnie claimed the individual title by a stroke.

Bud and Arnie settled into life at Wake Forest – swapping time between classes, social life and golf. In many ways, they had much in common; but these two friends also found that where one was weak, the other was strong.

“Socially and academically, Bud and I had a system of sorts worked out where we more or less looked after each other,” explained Palmer. “Our strengths and weaknesses beautifully complemented each other’s. I had a stronger physical constitution … Bud was shyer than me, so it was left to me to speak to girls … On the academic front, Bud had a strong work ethic and was forever on my case about keeping up my grade point average to avoid losing my scholarship and being put on academic probation, or worse, getting kicked out of school.”

Bud had something of a challenge on his hands. More than once, Arnie was asked to pay a visit to the dean’s office for “friendly chats about his casual academic performance.” But Bud’s constant cajoling and encouragement kept Arnie in the books and on the links.

Their second season, the team lost two matches and reprised its role as conference runner-up; Palmer again claimed the individual conference crown. And it wasn’t long before Wake Forest realized what they had in these two.

Being the good friends they were, the two often visited one another’s homes. When the college boys were under Mrs. Worsham’s roof, she served her famous fried chicken. The college men visited the golf courses the Worsham brothers frequented, and if they were lucky, Bud’s sister would make them cookies for the drive back to Wake Forest.

During their visits further north to Latrobe, the boys stopped by the country club where Arnie’s dad was the head golf pro. They’d play the “short, but imaginative” nine holes that Deacon Palmer had built with his own hands when he was a teenager.

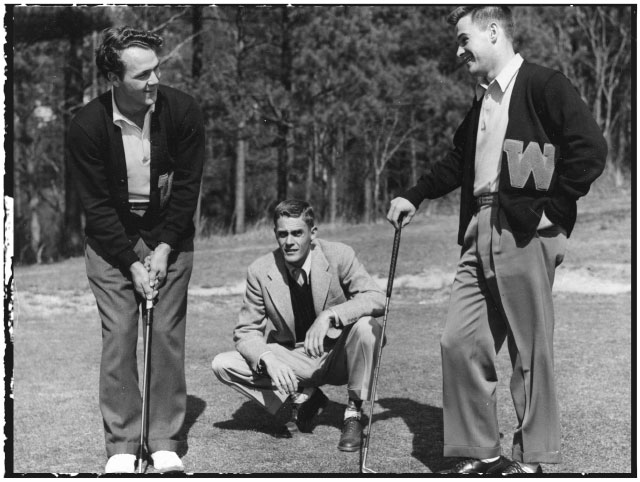

Arnold Palmer, Coach Johnny Johnston and Bud Worsham

While the boys and their families saw one another at tournaments across the country, the visits to each other’s homes solidified the bond. They knew one another’s parents, siblings and all the stories that made for perfect teasing fodder.

Then came their best year.

“My junior year at Wake Forest was, in retrospect, maybe the most fun of all my college years,” Palmer said. “There were lots of laughs and more competitive golf than I’d ever played in my life. Bud and I grew socially more confident but were still basically inseparable.”

That third golf season, the team went 13-1, losing only to the Tar Heels.

“Worsham, the number two man on the squad for the past two years, teams up with Palmer to give the Deacs a potent one-two punch,” wrote Wiley Warren (’52), a sports columnist for the Old Gold and Black.

Wake Forest took the Southern Conference title and competed in the NCAA tournament in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

If life had a pause button, this would be where the friends’ story would linger. But it doesn’t.

In the fall of 1950, seniors Bud and Arnie congregated with the Groves Stadium crowd for the Homecoming football game. Following a Deacon victory, the two walked back to their rooms with plans to get dinner and go to the dance, but Arnie fell asleep. Soundly. Bud shook Arnie awake, telling him that he and Gene Scheer (’53) were headed to the dance in Durham, and asking his best friend to go along. The groggy Arnie declined, instead trying to persuade Bud to catch a movie with him.

“Come on, Bud. Stay with me. Go to the movie.”

“No,” Bud said. “Gene and I are going to the dance.”

Neither would budge. Arnie fell back asleep, and Bud and Gene left in their fancy clothes, Gene riding shotgun as Bud rambled his 1938 Buick sedan down Durham Road toward the big dance.

When Arnie woke up the next morning, he noticed Bud’s bed hadn’t been slept in.

Less than 48 hours later, the last words the friends shared were a haunting echo. The dance was over, Sunday had passed, and it was Monday morning. Arnie sat on a train headed toward Bud’s home, the seat next to him empty. He stared out the window, bleary eyes affixed nowhere, combing through his memories as the scenery rushed by. Every now and then, he’d get up the courage to sneak a glimpse at the reality he so desperately wanted to be a bad dream. Near him, the casket was secure.

Bud didn’t stay.

On their way back from the dance, Bud and Gene were killed in a car accident.

After the devastating loss of his best friend, Wake Forest was not the same for Arnie.

“I thought I’d go crazy. I was always looking around for Bud,” he recalled.

Palmer left Wake Forest and enlisted in the U.S. Coast Guard. Following his military service, Palmer returned to Wake Forest to finish his education. He golfed with new teammates, but without Bud there to keep him on track, Palmer skipped most afternoon classes to play the game that would change his life. With success looming, he left school with an ACC championship and a few credits short of finishing his business degree. You know the rest of the story.

Before he became a legend, Arnie walked with Bud along the links of Old Campus. They set course records, teased one another about asking girls out and nagged the other one to hurry up and get his homework done so they could golf.

Before the tragedy and before the fame, Bud and Arnie were just kids. They were Wake Foresters. They were friends.

To read more about Bud and Arnie, visit our story.

Don't Check Your Heart at the Door

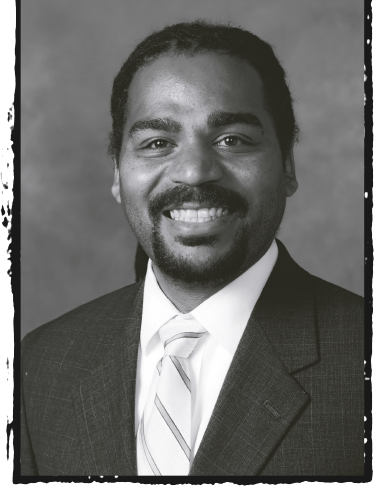

Dr. Nate French (’93)

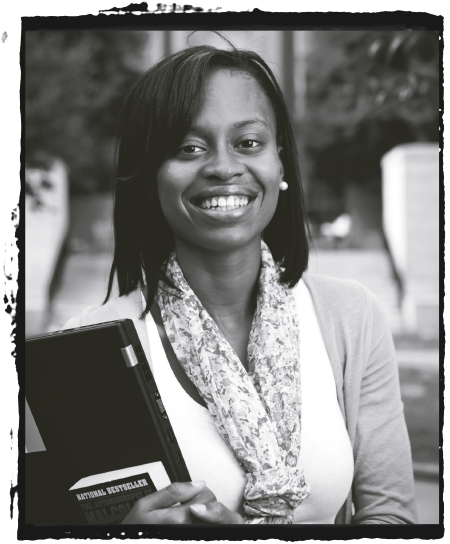

& Nicole Little (’13)

Dr. Nate French (’93) read through the next admission application on his desk. He was impressed by the multiple recommendations that shared this potential Wake Forest student was confident, assertive and an engaged social activist. This student was perfect for the first class of Magnolia Scholars, a scholarship program that supports first-generation college students. French prepared the acceptance letter.

Dr. Nate French (’93) read through the next admission application on his desk. He was impressed by the multiple recommendations that shared this potential Wake Forest student was confident, assertive and an engaged social activist. This student was perfect for the first class of Magnolia Scholars, a scholarship program that supports first-generation college students. French prepared the acceptance letter.

“I received a letter regarding the Magnolia Scholar program,” shared Nicole Little (’13). “At the time, I did not know what being a ‘first-generation’ student entailed, but I was happy to become part of a community of similarly situated individuals once I arrived on campus.”

Little, a native of Winston-Salem and graduate of Carver High School, was intent on becoming a doctor.

“I was knee-deep into the semester, taking general chemistry with Dr. Angela King, and did not do too well on the first exam,” explained Little. “Feeling defeated and after talking with others about the experience, I was encouraged to schedule an appointment to see French. And I did.”

After sharing about the abysmal test result, French asked Little one question: “Why do you want to be a doctor?”

No one had ever asked her that question before.

“Well, I want to help my mom financially,” the first-year student replied.

French chuckled and through his light laugh, he said, “You’re not going to be a doctor.”

The comment was startling. It stung.

“As a kid who came from tough circumstances, I was used to being counted out. In my mind, Dr. French was being added to the list of naysayers,” remembers Little. “Little did I know, he was focused on a bigger picture – one that I could not see at that time.”

“She was so mad at me,” laughed French. “She was mad at me for a good two years!”

In her sophomore year, Little started volunteering with the Darryl Hunt Project for Freedom and Justice, where she learned about racial disparities and became increasingly interested in how the criminal justice system operated.

“I grew passionate about social justice and wanted to be a change agent,” commented Little. “I wanted to be a lawyer.”

So, she returned to French’s office, head held high, to share her new plan. His response this time was different. “That’s great! You’re going to be an excellent attorney.”

She politely told French that she knew that and wanted to relay her new plans in person. The similar chuckle returned, and the mentor asked the student if she knew why he made the comment about being a doctor.

“He proceeded to tell me that he said I wouldn’t be a doctor because of the reason I gave him,” she revealed. “From our conversation, he could tell that I was not a person motivated by money. Money was not going to push me to get through long nights of studying organic chemistry. Based on his experience, people that become doctors were fueled by passion. Simply put, I wasn’t passionate about the work of being a doctor.”

“You hear students give all kinds of reasons for wanting to be something,” commented French. “At some point, I tell them that they can’t get through on anyone else’s motivation. You have to pursue what you want because you want to.”

Little graduated from Wake Forest as part of the first class of Magnolia Scholars. In 2017, she graduated from North Carolina Central University School of Law. She’s now an attorney in her hometown, and this past fall, she returned to Wake Forest to share her story with the 10th class of Magnolia Scholars.

“Nicole always really had a big drive,” stated French. “She just had a magnetic energy. She was one of those students that we knew was going to be really influential and instrumental for Winston-Salem.”

“Dr. French taught me that despite what the world tells us, it is okay to keep your heart and career in the same place,” stated Little. “You do not have to check your heart at the door.”

The two still stay in touch. “Dr. French and his family are a constant support to me – long after my graduation from Wake Forest. They are my extended family. I am forever grateful for them.”

Nicole Little (’ 13)

is an associate attorney at the law firm of Grace, Tisdale & Clifton P.A. with a practice focused on criminal defense. Prior to that, Nicole served as an associate attorney with a small criminal defense firm, handling a plethora of criminal matters, including traffic, violent and drug-related crimes in Forsyth and Guilford counties. Nicole, a sociology and women and gender studies major, serves as an advisor to Wake Forest University Expungement Clinic and National Poor People’s Campaign. She is a member of the Forsyth County Criminal Defense Trial Lawyers Association, Winston-Salem Bar Association and Association of Wake Forest Black Alumni, and she previously served on the City of Winston-Salem’s Citizens’ Capital Needs Committee and Parks and Recreation Commission.

Dr. Nate French (’ 93)

is the inaugural director of the Magnolia Scholars Program, which supports first-generation students at Wake Forest. He earned his bachelor’s degree in communication from Wake Forest and holds a doctorate in communication studies from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Throughout his career in higher education, he has worked in the admissions and financial aid areas as well as in the classroom. In addition to leading the Magnolia Scholars Program, he is an associate teaching professor in the Department of Communication.

Nothing Else Matters

The Wild Women

of Wake Forest

The white elephant gift had been stolen at least three times, and it was sure to have more temporary owners by the time the game ended and one woman secured the prize. The unwrapping and good-spirited thievery was only interrupted by one-liners, quick comebacks and bursts of laughter. The circle of more than a dozen women showed little evidence of the decades that had passed since their friendship began at Wake Forest.

The white elephant gift had been stolen at least three times, and it was sure to have more temporary owners by the time the game ended and one woman secured the prize. The unwrapping and good-spirited thievery was only interrupted by one-liners, quick comebacks and bursts of laughter. The circle of more than a dozen women showed little evidence of the decades that had passed since their friendship began at Wake Forest.

In the 1970s, New Dorm 2 and 3A housed most of them, and during those years at Wake Forest, the women planted seeds of lifelong friendships. Then, graduation came and life happened. Jobs, marriages, kids and busyness interrupted their connection. Decades passed, marked mostly by inconsistent homecoming reunions and Christmas cards. In 2001, when kids were older and life was a bit more stable, the women thought it was time to reconnect.

The first reunion happened in Cashiers, North Carolina, where one of them had a house. No longer the college students from New Dorm, these were dentists, doctors, lawyers, stay-at-home moms, real estate brokers, nurses, business professionals, writers, professional fundraisers and physician’s assistants.

“We are an eclectic group,” explained Janice (Kulynych) Story (’75), one of the 14 who call themselves the Wild Women of Wake Forest.

After that first trip, the event grew into an annual spring gathering, where a long weekend was spent hiking, shopping, playing games, biking, cooking a collective dinner and stealing white elephant gifts.

“Most of all, we would just sit around and talk and laugh,” remembers Story. “Wine may also have been involved!”

After eight or nine years in Cashiers, the women felt it unfair that one friend was always serving as hostess, so the annual trek to the North Carolina mountains became a floating reunion. Walking along a beach, sitting on a porch looking at a mountain or skipping rocks across a lake, the women would seek the comfort that comes from deep friendships. One year, the support, empathy and trust between the women were especially needed. At that gathering, one woman was going through a tough divorce, another faced breast cancer, and another’s child had passed away. In the midst of the revelry and reunion lingered the reality.

“We have had personal traumas, and this is the group that came together to support, listen and love,” revealed Story. “There is a depth to our friendship. No matter where we are or how old we are, we’ll always be there for each other.”

Between the official reunions, smaller subgroups of the Wild Women would get together. There’s a group who lives in Winston-Salem, a few who reside in Charlotte and a handful who are in Atlanta. Two or three in the group attend the U.S. Open Tennis Tournament in New York City every year. Others touch base in person when they are in town for business.

Naturally, the connections between their families grew also. Two children of the Wild Women dated once, feeding enthusiasm for a potential Wild Woman wedding. Two of the women introduced their widowed parents to each other, and they did end up getting married. And then there was the raucous gathering during the 2006 Orange Bowl in Florida, where, to the embarrassment of all their children, the Wild Women led a conga line through the restaurant, singing at the top of their lungs.

The trips are interspersed by long email chains passed between one another and flurries of text messages during Wake Forest football games. Facebook has helped keep them up to date, and the Christmas cards with grandchildren’s photos are always a highlight of the holidays.

“It’s a special and unique relationship to each one of us individually,” shared Story. “But it takes some work and commitment. We have to believe that Wake Forest fosters these kinds of relationships, but it takes the people to continue them. I tell my children to nourish their relationships because you never know what it’s going to grow into.”

In 2018, most of the Wild Women turned 65 years old. Story invited all of them to her home in Park City, Utah. A dozen of them made the trip, spending four or five days together.

“It was a celebration of looking at each other and saying, ‘You don’t look 65! You don’t act 65!’” shared Story. “We talked about when we turn 80, we are still going to be friends – and at least one of us will remember what we used to do!”

Forty-five years after they found one another at Wake Forest, after they lost touch and found one another again, the Wild Women of Wake Forest treasure their bonds of friendship.

“It’s not who’s got what or who goes where,” stated Story. “It’s about the people. Nothing else matters.”

The Wild Women of Wake Forest

Jan (Rosche) Aspey (’75)

Jennie (Bason) Beasley (’75, P ’07)

Cindy (Ward) Brasher (’75, PA ’76)

Vickie (Cheek) Dorsey (’75, JD ’78, P ’08, P ’15)

Lynn Killian (’75)

Kathleen (Brewin) Lewis (’75)

Debbie (Roy) Malmo (’75, MBA ’79)

JoAnne (Green) Marino (’75, P ’05)

JoAnn Mustian (’75)

Gail V. Plauka (’75)

Norma Pope (’75, P ’12)

Leslie (Hoffstein) Stevenson (’75)

Janice (Kulynych) Story (’75)

Becky (Sheridan) Williford (’75, P ’10, P ’13)

The Ride That Started Everything

Anil Rai Gupta (MBA ’92, LLD ’17) &

Ashley (Witcher) Simpson (MBA ’92)

the woman asked out her car window.

The man she stopped beside was headed home. Just weeks into his life in the United States, he didn’t have a car yet. He didn’t have community yet. He was in a new country, at a new school, pursuing a new dream.

He looked at the woman. She had been assigned the seat next to him in one of their MBA classes. She seemed nice; they exchanged greetings every day.

“Yes, please,” said the man.

The short ride ended, but an unlikely friendship between Anil Rai Gupta and Ashley (Witcher) Simpson began.

“The next day, when I met her in class, things were different,” Gupta remembers. “We talked much more. The acquaintance developed into a deeper friendship, and we started looking out for each other.”

Gupta, from Delhi, India, was one of few students from his country at Wake Forest in the early 1990s. He shared with his classmates that his family had an electronics company. He chose to come to the United States to earn his business degree so he could return to India and help with the family business. After that first class, they studied together and picked seats near one another in their other classes.

“Anil was humble and kind,” remembers Simpson, a North Carolina native. “He was very smart and had a knack for developing relationships with professors. He embraced his opportunity to be in the United States and absorbed as much as he could.”

“She was a very empathetic person,” remarked Gupta. “Given that I was so far away from home, having an understanding friend like Ashley really helped.”

Simpson introduced Gupta to her boyfriend, Sam, and the two men quickly became friends too. At Thanksgiving, Simpson invited Gupta to her family’s gathering in Greensboro. And when Gupta’s parents visited the United States, Gupta invited Simpson and other friends over for his parents’ spicy Indian cuisine.

“To this day, my mother remembers how Ashley stayed back and helped clean the dishes,” commented Gupta.

After graduation, Ashley and Sam married, and Gupta returned to India, where he met and married his wife, Sangeeta. Every now and then, the graduate school friends would get in touch, but it was limited.

In 2007, when the Guptas visited the United States, Wake Forest business professor Ram Baliga, and his wife, Gayathri, hosted a party in Winston-Salem, and the Simpson crew was there.

After that, the two lost touch again until the spring of 2019. Simpson’s daughter made plans to travel to India for a college project, and Simpson decided to track down Gupta. When word got to Gupta that an Ashley Simpson from the United States was trying to get in touch with him, he smiled and said, “My best friend from graduate school!”

“By luck, we were able to establish contact again, and we had a long chat on the phone,” Gupta said. “We recounted all of our memories. Though our contact was limited over the years, whenever it happened, it was like old times again.”

In April 2019, Gupta was presented with Wake Forest’s Distinguished Alumni Award. He and Sangeeta traveled to the United States for the event, but the rest of his family was unable to attend. On his guest list were two people: Ashley and Sam Simpson.

The Simpsons were taking their high school senior son on a spring break trip and would have to time planes and traffic just right in order to make it back. As luck would have it, the Simpsons returned to the Raleigh airport to a dead car battery. With the clock ticking, they found a stranger to jump the battery, made the trip back to Greensboro to drop off their son, and raced to Winston-Salem in time to celebrate with the Guptas.

“She and her family rushed back from their vacation for me,” shared Gupta. “It was overwhelming for me.”

A few days after that event, the Guptas gathered at the Simpsons’ home to catch up, look through old photos and celebrate Sangeeta’s birthday.

This past summer, the two families met in London and spent time together. Their children – Chandler, Sam, Isabelle, Aradhana and Abhinav – met. Over dinner, they exchanged numbers and planned to stay in touch. The families are planning another get-together in London soon, and hopefully, a visit to India will be in the Simpsons’ future.

“It is an unlikely friendship,” confessed Ashley. “If you looked at our MBA class and wondered who would be friends, it probably wouldn’t have been the two of us.”

“I guess when friendships are deep, they remain forever,” Gupta said with a smile.

Ashley (Witcher) Simpson (MBA ’ 92)

combined her interest in business with a love of art. She currently owns and operates New South Portraits, where she represents artists of national and international distinction. The company, based in Greensboro, North Carolina, specializes in uniting clients with artists to create pieces of work in a variety of media. Simpson works with artists and clients throughout the United States and in Europe.

Anil Rai Gupta (MBA ’ 92, LLD ’ 17)

transformed a small electrical equipment company into Havells, a global powerhouse. But his impact is seen beyond the electric lighting, fans and appliances found in countless homes and businesses in India. Since Gupta graduated from Wake Forest and took the helm at Havells, he has instituted a midday meal program that feeds about 60,000 schoolchildren every day. He also launched several initiatives that address serious personal health challenges in India and help replenish natural resources through sustainability efforts, and he co-founded Ashoka University, India’s only liberal arts institution. In 2019, Gupta was named Entrepreneur of the Year by Forbes India.

Teach Hard, Love Harder

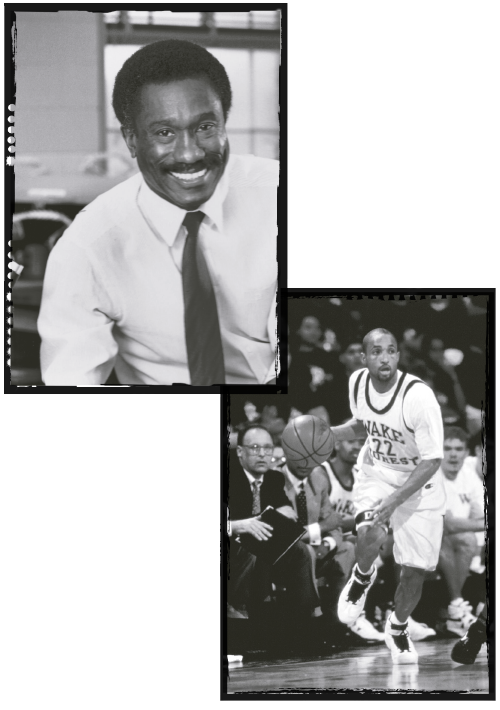

Dr. Herman Eure (Ph.D. ’74) &

Randolph Childress (’95, P ’20)

Bam! The door slammed open and a seemingly serious, formidable figure walked to the front of the room. The collection of six first-year basketball players snapped to attention, postures straight and eyes glued on the man. Who was this guy?

Bam! The door slammed open and a seemingly serious, formidable figure walked to the front of the room. The collection of six first-year basketball players snapped to attention, postures straight and eyes glued on the man. Who was this guy?

“Let me tell you something,” started the man, “I don’t care that you play basketball. I don’t care if you’re good or not. I care that you sit in the front of class. I care that you get good grades. And I care that you hold your head up high.”

The guy was Dr. Herman Eure, and in his audience was Randolph Childress.

“That was the first introduction,” laughed Childress, “and I thought, ‘I’m never taking his class!’ But he resonated with us.”

For years, Eure, a biology professor, met the first-year basketball players when they arrived at Wake Forest. He set the expectation early that they had a responsibility to themselves as people, not just as athletes.

“My concern as a black man was that these young men do something with their lives,” he explained. “I knew that most of them would never earn a nickel playing ball professionally, and I wanted to give them a reality check. What would they do from 25 to 80 years old?”

After that first meeting, Childress did his best to avoid the professor, but college graduation requirements had other plans. In the summer before his sophomore year, Childress was in Eure’s biology class.

“I’ll never forget what he said to me that first day of class,” remembers Childress. “It stuck with me. He said, ‘I watched you play basketball. I see a confident person that feels like he’s as good as anybody on the floor, but when I see you walk around campus, I don’t see the same person. I need you to be as confident and competitive as you are on the basketball court in my classroom.’”

“What I wanted was for him to do well,” explained Eure. “Don’t try to sell me that you can’t be intelligent and hardworking in the classroom when I see you doing it on the basketball court.”

After that first meeting and that first class, Eure and Childress connected quickly. Eure was a mentor to many students, and they would often gather at his house to eat and talk through what was going on in life. Around Eure’s table and in every conversation with him, students knew to expect one thing: honesty.

“He was someone from a male perspective who looked like us, who challenged us and who motivated us,” recalled Childress. “It worked.”

“For me, Randolph was another one of my children,” commented Eure. “It’s my responsibility as a black man to tell him what I know. Some things you have to find out on your own, but there are other things that I can help with along the way.”

And when it came to some big decisions that Childress had to make – entering the NBA draft, playing professionally in Europe, returning to Wake Forest to coach – he stopped by Eure’s office or found himself at Eure’s kitchen table.

“When you make important decisions in your life, we all have people we’re going to bounce those ideas off of,” said Childress. “You want an honest opinion. He was a rock that I could always come back to.”

As the years passed, the connections between Eure and Childress grew. Eure was Childress’ mentor. Childress was a role model to Eure’s son, Jared. Jared taught Childress’ son, Deven, in high school, and the younger Eure became the younger Childress’ mentor. And when it came time for Eure’s grandsons – the Martin twins from Davie County – to decide if they should enter the NBA draft, Eure recommended that they talk to Childress for his advice.

“You can’t make it up,” laughed Childress. “We’re connected for life. It’s been an unbelievable journey, and there’s more to come.”

Now, Childress is coaching the players who sit where he once sat, and he’s taken a few lessons from his mentor’s playbook.

“I tell my players now that I coach them hard, but I love them harder.”

Herman Eure (Ph.D. ’ 74)

was a biology professor at Wake Forest for nearly four decades and was regularly recognized for his distinguished teaching. He was the first African American graduate student on the Reynolda Campus, and at age 27, was one of the first African Americans to join the faculty. Some of his early contributions to campus have evolved into what we now know as the Intercultural Center and Magnolia Scholars, and his overall influence at Wake Forest was celebrated in 2017 when he received the Medallion of Merit, the highest honor bestowed by the University. In his retirement, he serves Wake Forest as vice chair of the Board of Trustees.

Randolph Childress (’95, P ’20),

one of the most iconic basketball players in Wake Forest history, delighted fans during his college career in the early 1990s. The Washington, D.C., native was selected in the first round of the 1995 NBA draft by the Detroit Pistons with the 19th overall selection. After two seasons in the NBA – one with the Pistons and one with the Portland Trailblazers – he played professionally for 14 more years in Turkey, France and Italy. He returned to Wake Forest in 2012 and currently serves as associate head coach of the Wake Forest Men’s Basketball Team.