Strength in Numbers

Like many Wake Forest students, Kathryn Webster (’17) had a plan. She wanted to be an actuarial scientist. She wanted to attend law school. She wanted to get her MBA, become president of the United States and launch a global nonprofit.

And she wanted people to understand that being visually-impaired would never stop her from dreaming big.

The following story chronicles Kathryn Webster’s (’17) experience during her years at Wake Forest. She is now thriving as a business analyst at Deloitte in Washington, D.C.

Strength in Numbers

Kathryn Webster (’17) was born blind, but a complex operation when she was just 16 days old gave her some vision in her right eye. Then, 10 days before she turned 13, the limited vision Kathryn had disappeared.

In front of Greene Hall, there’s an air vent. It runs 24/7 and makes a constant humming noise. It’s a sound that for many simply blends into the background of an active campus. For Kathryn Webster (’17), it’s her own personal compass.

That air vent is her true north; it’s how she knows where she is on campus. The louder the humming, the closer she is to Greene Hall. If it’s in front of her to the left, she’s somewhere near Carswell, and if it comes from behind her to the right, she’s probably headed toward Tribble, where even the most directionally savvy regularly meet their match. Yet that corner of campus is critical for Kathryn. It reminds her where she is, where she came from and where she can go.

Thousands of Wake Forest students know Michael Shuman. Last year alone, 1,652 of them stopped by the Learning Assistance Center (LAC) to visit him and the staff. They were there for various reasons — to request a peer tutor to prepare for an upcoming exam, to get some helpful hints to strengthen study skills or to discuss accommodations for a class.

Kathryn Webster was one of those students. She visited the LAC to follow up on if a student had requested a Latin tutor or to consult with Dr. Shuman about a course on her schedule. Michael, as Kathryn has come to call him, was the first person she got to know at Wake Forest.

They were introduced over the phone after Kathryn decided to become a Deacon and spoke weekly during the summer of 2013. When Kathryn arrived on campus that August and they finally met in person, the two had already become good friends.

“She’s one of the only students who has my cellphone number,” Michael smiled.

“He calls me Kate,” said Kathryn proudly. “That’s what a lot of my family calls me.”

That first day on campus, Michael gave Kathryn and her guide dog, a mostly focused black lab named Enzo, a tour of campus to identify key landmarks — like Wait Chapel, Reynolda Hall, Farrell Hall, and later on, that noisy vent.

Like many Wake Forest students, Kathryn, a junior from Greenwich, Connecticut, has a plan. Or more accurately plans. She wants to be an actuarial scientist. She wants to attend law school, but isn’t sure if she’ll actually do it. She wants to get an MBA, and that’s probably going to happen. She wants to be president of the United States and start a nonprofit and travel around the world. And she’s just getting started.

“She doesn’t know her limits. You tell her she can’t do something, and forget it.” — Kathryn’s mom, Monica

“She doesn’t know her limits,” Kathryn’s mom, Monica, chuckled. “You tell her she can’t do something, and forget it.”

She’s been like that since the beginning, with home videos to prove the stubborn side her family and friends know so well. There was the time she was on a slide and turned her back on the camera when told it was time to come in. Then there was the time on the ski slopes when the seven-year-old decided the tether was more of a suggestion. In fourth grade, Kathryn, an aspiring a horseback rider, adamantly rejected the idea of a participation ribbon. “I found something that I can compete in,” she told her mother, “I want to compete.”

She was just like every other kid. Except she wasn’t. Kathryn was born blind, but she hasn’t always been without sight. When she was 16 days old, a doctor diagnosed her with bilateral microphthalmia — both eyes were abnormally small. She had absolutely no vision in her left eye, and there was nothing to be done about it. But when she was still days old, a glaucoma specialist performed a complex operation where he sliced open the pupil of her right eye to allow light in. With glasses, Kathryn’s vision was corrected to 20/70.

So she rode horses, got teased by her brother, snowboarded, learned mental math from her dad, became a cheerleader, tested her mom with her willfulness, joined Girl Scouts, discovered she was a good student, ran track and took piano lessons.

Then, on Easter Sunday — March 23, 2008, to be exact — Kathryn woke up, tears streaming down her face.

“I rubbed my hand across my eyes,” Kathryn explained. “My right eye was inflamed to the size of a baseball. I couldn’t open it; I couldn’t see. My thoughts were racing. I couldn’t fathom the possibility of total darkness.”

Monica whisked her 12-year-old daughter to her doctor’s office at the eye center. Because it was a holiday weekend, Kathryn’s typical doctors were not there. Those on call did their best to perform emergency surgery on her eye, but complications arose — a popped blood vessel and a detached retina. Ten days before she turned 13, the limited vision Kathryn had disappeared.

“She used to tell me on a daily basis, ‘Mom, do not give up,’” Monica remembered.

Kathryn and her family traveled the country searching for answers that could improve her eyesight. Since that Easter, Kathryn has endured 21 surgeries on her right eye, including four cornea transplants. The most recent surgeries occurred her first year at Wake Forest. Every day, her vision is different; it is some combination of light, color and shapes.

Kathryn returned to middle school, intent on keeping much of her life the same. She was still a cheerleader; now she simply used the Velcro-like tape on the floor to find her spot in the formation for the basket toss. She was a short distance runner on the track team. Using the outside lane, she raced toward her coach standing at the finish line wearing a bright orange jacket so she would know when to stop.

All this proving yet again that the only thing capable of stopping Kathryn is Kathryn.

“Kathryn had the option to attend several universities based on her academic achievements,” Kathryn’s dad explained.

Ivy league schools, high-end liberal arts colleges — she could basically go anywhere. She visited schools in North Carolina — halfway between her mom in Greenwich and her dad in Florida, and just the right distance from her brother, Alec, at the University of Virginia. After her whirlwind college odyssey, she quickly knew which ones were off her list and which had risen to the top.

“After visiting Wake Forest, I left the state not finishing the rest of the school tours. I knew I wanted to come here,” she smiled.

She applied, and anxiously awaited word. On the day she thought an answer might reach her mailbox, she excitedly texted her mom: “If there’s a package from Wake — whether it is thick or thin — do not open it! I want to feel it before anything else.”

When she got home, Kathryn’s hands told her it was an excitingly thick envelope. Her mom saw the “Congratulations!” written across the front.

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 is federal legislation intended to prevent discrimination of people with disabilities. It states that colleges and universities are obligated to provide “reasonable accommodations” that would allow students with disabilities to participate in the college experience. Like most institutions, Wake Forest meets that need, providing resources through the Learning Assistance Center and Disability Services. Decision made and deposit sent, Kathryn contacted Michael Shuman.

"Providing access to a course that relies on more than just text would be a challenge.” — Michael Shuman

“When I knew Kathryn was coming to Wake Forest, I learned that she already had a good bit of experience in math from high school,” Michael stated. “She was coming to Wake Forest as a pretty advanced math student. When she expressed an interest in mathematical business — something that was more than a basic math course — it gave me pause. Providing access to a course that relies on more than just text would be a challenge.”

Kathryn’s dream of becoming an actuarial scientist meant she needed to master high-level math. As an incoming student, her AP exam scores made it possible to skip the entry-level stats class, so she enrolled in the next course in the curriculum, MTH 256: Statistical Models.

“It’s a visually rich course with scatter plots and bar graphs,” explained Michael, who has spent 18 years of his career at Wake Forest. “It’s a class that says, ‘Take a look at the data. What do you see?’ When Kathryn came in the fall, I asked her to postpone taking the course because I just didn’t know how to do it.”

Putting off the course for one semester allowed Michael to seek out a way for Kathryn to achieve her goal. The topic would require more than simply converting a textbook into a Braille format. That fall, he attended an assistive technology conference where he consulted with experts in the field of accessible education. They offered suggestions, but no real solutions. He contacted colleagues from other institutions to see if they had experience that Michael didn’t have. They, too, offered some ideas, but again, no real answers.

“I always came back to the drawing board thinking there’s still so much I don’t know how to teach.”

Holding his breath, Michael clicked the send button. Then he exhaled. The message, referring to MTH 256, landed in Dr. Robert Erhardt’s inbox.

“I got this novel of an email,” recalled Rob. “I get a lot of emails so I scan them quickly. I interpreted the email basically as, ‘What book do you use?’ I wrote back the title of the book.”

Several people were on the email chain, and one kindly suggested Rob might need to re-read the message.

“I missed the fact that Kathryn couldn’t see,” Rob confessed. “I read it again and realized it was a much bigger deal than I was prepared for.”

In October, Rob and Michael met the first time to talk about Kathryn’s participation in the visual stats class. They had to create a way to help Kathryn master the three major objectives required of all students who take that course: interpret and produce mathematical writing; interpret and produce computer code; and interpret and produce images and graphical displays.

“We started with the most scientific first step we could think of,” Rob explained with a grin, “we Googled to see what other people had done. We got nothing.”

It was during one of their several meetings that Rob and Michael looked at one another bewildered. As they rehashed all Kathryn would need to be able to do in the course, the only thing they were sure of was that they would not give up.

It was Rob’s turn to send an email. On November 7, 2013, after riding his bicycle to the office, the assistant professor took to his keyboard and introduced himself to Kathryn. “I’m starting to prepare,” he wrote, “and it would be helpful for me if we could briefly meet so I can learn a bit more about how to best get you materials for class.”

They agreed on a time to get together, and the first-year student assured him that math was one of her strengths. “I truly can’t wait to meet you and discuss any and all obstacles that are potential concerns for either of us,” Kathryn replied. “Thank you very much for your time. I am grateful that we are touching base in advance so January won’t slap us right in the face.”

Kathryn recalls that first email exchange with a smile. “The fact that Dr. Rob reached out to me first gave me that extra feeling of comfort and security,” she said, using her nickname for the professor. “Typically, I email my professors, introduce myself and assure them about having me as one of their students. This statistics professor, though, made that initial introduction, and to this day, I am so grateful.”

“So, picture this: We’ve got a nerdy actuarial scientist turned professor who loves statistics; we’ve got a college administrator who would gladly give anyone the shirt off his back; and we have me — a freshman girl still feeling out this place.” — Kathryn Webster

One Thursday morning in November, the three huddled together around a small circular table outside Dr. Rob’s office in Manchester Hall.

“So, picture this: We’ve got a nerdy actuarial scientist turned professor who loves statistics; we’ve got a college administrator who would gladly give anyone the shirt off his back; and we have me — a freshman girl still feeling out this place,” Kathryn described. “We were all wrestling with this idea of me not only being able to succeed in this specific course, but fully comprehend all of the material. Uncertainty was an understatement, but there was no backing down.”

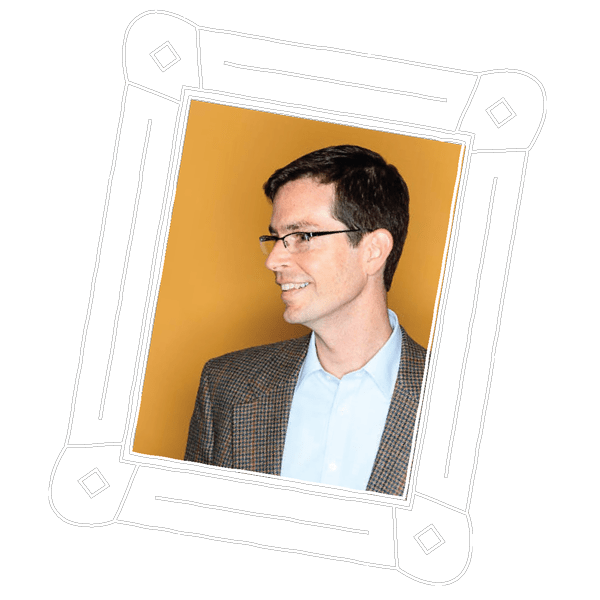

Robert Erhardt and Michael Shuman with Kathryn Webster ('17).

In conversations marked by openness and candor, it was apparent how independent Kathryn hoped to be. She didn’t want a reader for the course. Didn’t want a scribe. Didn’t want less work.

“I wanted to do all the work, and I wanted it done all by myself,” she stated. “That is exactly what the three of us needed to figure out.”

Kathryn’s confidence crossed the table to the two men and over state lines to reach Monica. “If there’s one thing in life I love, it’s math,” Kathryn told her mother. “I’m going to do this.”

The three started gathering information. Dr. Rob researched blind statisticians and the software they used; the professor found two blind statisticians in his search — one in New Zealand and one in South Africa — but no blind actuarial scientists. Michael worked on the accessibility side; the interim director found a varied range of technology that could produce tactile graphics. Kathryn was tasked with finding other students who have faced similar struggles in higher education; the aspiring actuarial scientist found no one with that experience to walk her through the process.

It was then they knew that they would need to pioneer a solution for Kathryn. One by one, they addressed the three objectives she would need to master.

First, Kathryn would need to interpret and produce math.

High-level math can be typed on a computer in LaTeX, a special language that conveys mathematical and statistical material. LaTeX uses ASCII characters — braces, brackets, underscores, ampersands, Greek letters. ASCII characters can be conveyed using Braille.

Across that circle table, Dr. Rob and Michael looked at Kathryn. She smiled; she reads Braille.

So, a bridge between Kathryn and math was built: math to LaTeX to ASCII symbols to Braille to Kathryn. The only hiccup was that Kathryn would have to learn LaTeX — used by high-level mathematicians and statisticians — in her first year of undergraduate studies. It was already November; the class started in January. She would have her winter break to learn it.

At that assistive technologies conference that Michael attended, he asked colleagues if a student could learn LaTeX in a few weeks. Many said it wasn’t possible.

“There was this moment,” wondered Dr. Rob, “is she going to want to learn LaTeX? It’s not a natural way to learn introductory mathematics. The answer is yes. She did.”

In the span of a few weeks, Kathryn familiarized herself with LaTeX so she could focus on the stats content just like the rest of her classmates.

So there it was. The answer to the first question.

“You wrestle with a problem for awhile, and you see the first time a solution is successful,” explained Dr. Rob. “Then you play the same game again. You have no idea what you’re talking about until Kathryn sits right there. Those were the key moments. There wasn’t one of them; there was a series of them. You get your first success, and then you can build on that.”

The next hurdle was interpreting and producing computer code.

Statisticians use the software program, R, to do their work, and undergraduates in Dr. Rob’s course are introduced to it via the version called R Commander.

During one of his many Google searches, Dr. Rob found Jonathan Godfrey, a faculty member and blind statistician at Massey University in New Zealand. Godfrey has spent a good portion of his career making statistics more accessible to individuals who are blind, most notably by developing BrailleR, a program — almost like an app — that interfaces with the regular R software, modifying the computer to be more seamless for users. Instead of R Commander, Kathryn used R Terminal, the computer coded view of R, and applies BrailleR to describe the visual models on the screen.

To complete her assignments, Kathryn needed to have multiple screens open on her computer at once — R, BrailleR and a running log of her work — so she could toggle between them. Instead of a mouse, Kathryn uses Alt + Tab to switch screens. In his research, Godfrey noted that R had a significant shortcoming; once you leave R, you cannot return to that screen to work. The cursor disappears, and the software freezes.

“The problem for someone who is blind,” Dr. Rob started, “is that they need to be able to bounce between the R window and the log. R didn’t let them. Conventional wisdom said, ‘We were so close, but people who are blind are not going to be able to use R.’ That was the message.”

“We’re so close” wasn’t a response that the actuarial scientist-turned-educator was willing to accept. In order to better understand how Kathryn would complete her work, he tried to see the situation from her perspective.

“I was sitting at home in my dining room, and I was imagining, ‘What is this going to be like for Kathryn?’ I literally had my eyes closed,” remembers Dr. Rob. “I had the robotic screen reader going, and I would get lost. It’s really, really hard.”

But hard doesn’t mean impossible. “You need to get people to really imagine what it is going to feel like from others’ perspectives,” Dr. Rob stated. “That’s where solutions come from.”

Just like Godfrey had described, when Rob tried to switch between screens, the program froze. Eyes closed, he could now fully understand the frustration. Removing his hands from the keyboard in defeat, he accidently bumped the Alt key. Suddenly, the cursor reappeared, and he could make R function again.

Dr. Rob immediately emailed Godfrey. The New Zealand scholar had recently written a paper explaining the drawback with R and its routine freezing. Rob’s email explained the serendipitous Alt key discovery.

Godfrey tried Dr. Rob’s solution on computers across New Zealand, and within three days, Godfrey confirmed it. He contacted his editor to stop the presses on that article. They were about to tell people they couldn’t do something — only now they could. Together, Godfrey and Dr. Rob wrote an addendum offering the Alt key solution to blind statisticians around the world.

“This update may seem trivial to some readers, but it is hugely important to blind users of R,” Godfrey wrote in that addendum. “Blind users… are back on par with their sighted colleagues.”

In solving a problem for Kathryn, the Wake Forest team unlocked another door for all who are visually impaired.

One last challenge remained: interpreting and producing images and graphical displays. On nearly every page of that stats textbook, there’s a graph. How would Kathryn see the visuals in the book, on the board during classroom discussions and on exams?

A dance of trial and error began.

What about drawing the graphs with puffy paint?

No. “Puffy paint takes like an hour to dry,” Dr. Rob said.

What about plastic paper that you draw on and the pen strokes produce a raised image?

No. “You’d have to draw all the graphs backwards,” Kathryn frowned.

What about PIAF — pictures in a flash? Draw on special paper and put it through a toaster-like heater. As it is heated, the paper blisters wherever there is ink.

No. “They are pretty crude drawings,” Michael explained.

What about a thermo pen? Using that same special heat-sensitive paper, draw with a hot-tipped pen.

No. “It would fade too quickly,” Kathryn answered.

Any number of devices and methods were considered in attempts to give Kathryn the ability to work with course material.

Then, they pursued more high-tech solutions and settled on a Braille embosser — a printer that produced Braille images and documents. Dr. Rob slipped a piece of paper in front of Kathryn. Her fingers ran over a sample graph. First the axes, then the plots.

“I remember I gave her the first one, and she said, ‘There are 30 data points,’” Dr. Rob grinned. “She literally counted the number of dots that showed up. It’s not until you watch Kathryn use one of those images and tell you what’s going on that you know it worked.”

“Not only was I able to succeed in the class while understanding all facets of the statistical subject matter, but I gained a greater sense of confidence in my future. Michael and Dr. Rob redefined what teamwork truly is; it was only because of the skills and passion that each one of us brought to the table that we were able to conquer this struggle.” — Kathryn Webster

“Not only was I able to succeed in the class while understanding all facets of the statistical subject matter,” commented Kathryn, “but I gained a greater sense of confidence in my future. Michael and Dr. Rob redefined what teamwork truly is; it was only because of the skills and passion that each one of us brought to the table that we were able to conquer this drawback.”

“I would like Kathryn to feel — and she knows — that she did it,” Dr. Rob said. “People helped her because they thought she could do it, and they believed in her.”

The team was three for three.

Necessity is the mother of invention, they say, and for Kathryn, Michael and Dr. Rob, that proved true. They came up with a solution, not the solution. And nowhere along the way was it guaranteed to work.

“I think Rob and I played it cool in the beginning,” admitted Michael, “but we were figuring this out as we went.”

“We might seem confident now, but we had a lot of uncertainty for a long time,” agreed Dr. Rob. “Michael and I would look at one another and say, ‘I don’t know. What do you think?’ He was my barometer. What does reasonable accommodation mean?” continued the professor, who kept his hands in his pockets to lecture so as not to rely on gestures for explanation. “Michael has infinite patience; he never runs out, it seems. He just wants to help people all the time.”

“There was no way any of us could have done this by ourselves,” Michael added.

Though the two men repeatedly remind others they just followed the law and did the right thing, the law doesn’t mandate perseverance or legislate kindness or deliver creative solutions. All the thought, compassion, discussion, preparation and extra time wasn’t devoted to fulfilling a law or teaching statistics. They did what they needed to in order to educate their student.

“Our job was to teach Kathryn,” Dr. Rob said simply. “So we taught Kathryn.”

After that semester, Michael and Dr. Rob published an article in the Journal of Statistics Education. Because of their experience, they’ve been able to share with others that it is possible to shape a course that relies on visual content for a student who is blind but wildly interested in the topic. Because Kathryn was a sample size of one, it’s unclear how this would work for other students in other courses.

“I sometimes fear it’s not going to work with other students that are blind,” Dr. Rob admitted. “I fear that it had more to do with Kathryn and who she is as a student — how hard she works, how much ownership she takes over her studies. I think she learned it because she’s Kathryn.”

“Society frequently questions whether blind students have the capabilities to succeed in the classroom,” remarked Kathryn, who declared a major in business and enterprise management with minors in statistics and computer science. “Many view blindness as a barrier to success, rather than a slight nuisance. Dr. Rob and Michael, like so many other members of the Wake Forest community, treated me as an equal. They believed in me. They put forth the energy and effort so I could excel, just like everyone else. They helped me stay determined and inspired me. To them, I was never a blind student. In their eyes, I am Kathryn, simply a student who loves to learn.”

The window of Dr. Rob’s office on the third floor of Manchester Hall looks out toward the Magnolia Quad. One of the first things you see — and hear, if the window is open — is that air vent outside Greene Hall.

That place is critical for Kathryn. It’s where Dr. Rob’s office is; it’s where Michael and Dr. Rob and Kathryn sat around a table and tirelessly developed a way to succeed; it’s where they solved problems, where they laughed, where they became friends.

“Wake Forest University professors care,” Kathryn smiled. “Dr. Rob sets higher expectations for me, which makes me feel good because I aspire to do what he did. He believes in me; he has confidence in me. The bar is set very high, and that’s a good thing. And Michael is always pushing my independence. He made it very clear from the beginning that he’s always available, but in the real world, I’m going to need to be able to fend for myself. He pushes me in a way that says he’s still there, but that I can do it.”

This rather unassuming corner of campus reminds Kathryn where she is — in a community that deeply cares about each individual student. It reminds her where she came from — a near-impossible situation turned possible through the efforts of many. And it reminds her where she can go — anywhere she wants.

Home

Home

Audio Version

Audio Version