In high school, Zach Gordon (’16) was considered the top tight end recruit in the state of Georgia. He came to Wake Forest for the academics, community and opportunity to play the game he loved, but he walked away with so much more.

Saturday, August 16, 2014

After being redshirted my first season and then playing in all 12 games during the 2013 season, I was looking forward to another fall of football. Pre-season camp was coming to an end, and the craziness of the season was about to begin. On Saturday, Wake Forest Athletics hosted Fan Fest where players and fans meet for a fun evening on the field, and my parents came to visit that weekend.

Sunday, August 17, 2014

The next morning, I woke up, told my parents goodbye, and headed to the football offices to get ready for our last team scrimmage of fall camp. My teammates and I were going on our 17th straight day of football, and we were ready to complete this scrimmage and start preparing for the school year ahead.

The scrimmage began at noon.

About 1:00 p.m.

Roughly an hour into the action, I was put in.

I was running a passing route across the middle of field, and I turned to see that the ball was thrown to me. The ball was high, so I jumped up with my arms extended and attempted to catch it.

As I was in the air, a defender ran and hit me in the chest, right below the sternum. The impact of the hit whipped my head forward violently. Right at that moment, I knew I had the breath knocked out of me. But something felt different. I’ve had the breath knocked out of me many times, and this was different.

After the hit, I fell on my side and rolled to my back. That’s when I felt like a really hot blanket was placed over my entire body.

Sunday, August 17, 2014

00

Months

00

Weeks

00

Days

00

Hours

01

Minutes

After the Hit

The trainers and team doctors rushed onto the field to check on me. After a few moments, I got my breath back, and the trainers told me to get up so we could get off the field. That’s when I tried to move.

I couldn’t.

I tried to move my legs. I tried to move my arms. Nothing.

When I told the trainers that I couldn’t move, I don’t want to say chaos ensued, but it felt a lot like that. They started conducting tests on the field. They grabbed my hands and asked me to squeeze their fingers, but I couldn’t. The only way I knew that they were grabbing my arms or holding my legs was because they told me.

I had no feeling or movement below my neck. The only thing I could feel was my head, and there must have been five different people touching my head to keep my head and neck as stable as possible.

It’s difficult to put into words what was going through my head at the time. I was terrified, shocked, uncertain, confused, and even angry. Here I was, a 20-year-old Division I football player, in the best shape of my life, lying motionless on the ground.

This wasn’t supposed to happen to me. It didn’t make sense.

Somehow the equipment managers were able to pop my helmet off. Then, an EMT put a big brace around my neck, and I was loaded onto a stretcher that I remember the EMT told me I was too big for. As a 6'4", 245-pound football player, I couldn’t fit onto most stretchers.

In what seemed like minutes after the initial hit, I was loaded into the ambulance and headed toward Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center.

I pray that no one has to endure an ambulance ride like that. The EMT kept asking me questions about what I could and could not feel. One of the trainers was riding with me and asked for my parents’ cell phone numbers. They were on Interstate 85 South headed back to Georgia when my injury occurred. I remember knowing the numbers off the top of my head, but I didn’t want to say them out loud. I didn’t want my parents to receive that phone call on their way home. Eventually, I gave it to him, and shortly after, we arrived at the hospital.

I was wheeled into the trauma unit of Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center. As soon as I crossed the threshold, a nurse put her hands on my head and told me that there would be a lot of people asking me the same questions and conducting the same tests.

I was stripped of all my football equipment and clothes and placed on a wooden board to keep my back and neck as straight as possible. Then, two nurses greeted me and took me to an area of the hospital where my first scan was going to take place.

Everything had happened relatively quickly after the hit. I was in complete and total shock. I had no feeling or movement below my neck, and I didn’t know if I was going to walk – or even feel anything – again. But I had peace.

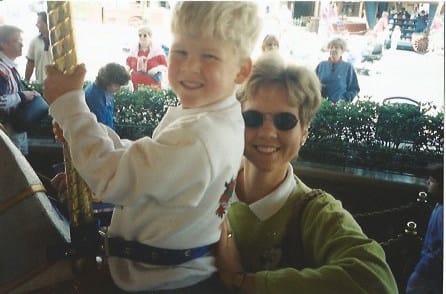

In my family, a symbol of God being near is the sight of a butterfly. At the time of my injury, my older sister, Allison, was teaching in Savannah, Georgia; my older brother, Andrew, was teaching in Honduras. Being so scattered – Winston-Salem to Savannah to Honduras – something as simple as a butterfly has always reminded my family that even if we are not physically together, we are still together. Seeing a butterfly lets us all know that God is with us; we are safe and protected.

As I was being wheeled into the room where I had my first scan, I was still lying straight on my back and all I could see was the ceiling directly above me. I will never forget this moment. I could see the hands of the trauma nurse who was holding onto my bed as she wheeled me through the hospital, and on her left wrist, she had two little tattoos of butterflies.

It was then – in my darkest moment – that I knew that God was right there. I had absolutely no idea what was going to happen to me. I couldn’t feel anything below my neck, and to be honest, I didn’t know what was even going on, but I knew that He was right there with me, and my whole family was there, too.

The first scan was conducted and took about 30 minutes. As I was wheeled back into the trauma unit, I saw my parents. Although unable to move, I saw them looking me over and holding my head. The only thing I could feel were their fingers running through my hair.

With tears in my eyes, I told my mom that I couldn’t feel anything. I couldn’t move.

My mom put her hands around my head, looked straight into my eyes and said, “Zachary, God is here. He is here.”

My dad, a family physician in Carrollton, kept close to me, giving me his strength and steadiness. He did not offer up his professional opinion. He let the doctors handle my situation, and I can only imagine how difficult it was for him not to weigh in with his thoughts.

Doctor after doctor continued to come in and out of my room, asking the same questions and doing the same tests. I was asked if I could feel my toes; I was poked and prodded in areas I need not say.

And still, I had no feeling.

Shortly after my parents arrived, I was taken into another room for an MRI. For three hours, the machine scanned me to my core.

It was going on nearly four hours since I had been hit. I still had no feeling or movement in my body.

After the MRI, the neurosurgeon came into my room in the trauma unit and said that no permanent spinal damage had been detected from the scan. There was no broken vertebrate and no narrowing of the spinal column. The doctors were very happy about that but confused at the same time because something severe happened. They just didn’t know what it was exactly.

So we waited.

More time passed, and doctors conducted the same tests. They poked my feet, my legs, my hands and asked the question I was beginning to hate: “Can you feel what we’re doing?”

I gave them the answer I was beginning to hate: “Still nothing.”

With more questions than answers, I was transported to the ICU at Wake Forest Baptist and spent the first night there. My parents sat on either side of my bed – waiting, watching, holding my hands. They held the phone to my ear so I could talk to my brother in Honduras, my sister in Savannah and my girlfriend in Athens. Emotions ran high in those conversations; it was so hard, and yet so great, to hear their voices.

And that’s when it happened. Something in my right hand – the hand my mom clutched. The hand that I always held as a little kid I could now finally feel again. I cried with my mom when I told her I could feel her hand.

Shortly after that, I got a weird feeling in my feet – almost like I was being stung by a swarm of bees.

There was so much emotion. So much excitement. So much joy.

Later that night, still in the ICU, I was able to wiggle my right big toe. Then, I was able to lift my arms off the bed just a little bit. Feeling slowly started to come back throughout my entire body, but it was very sporadic. It was as if my body was a huge computer that was shut off after going non-stop for 20 years; gaining feeling and movement back was a slow process of rebooting.

Family members, loved ones, coaches and what seemed like the entire football team visited me in my hospital room. I was absolutely overwhelmed by the number of people who came to see me and the number of people from my hometown who sent their prayers and support.

In between all of the visitors, doctors continued to monitor my progress. Nurses stopped into help with various tasks. I can vividly recall a time when a nurse had to bathe me because I didn’t have the strength to do it myself. I was so embarrassed. A 20-year-old shouldn’t need someone to bathe him. But at this point in my life, I did. The nurse was so sweet and supportive, but on the inside, I was torn apart by the fact that I needed help cleaning myself.

Therapists followed. They began working with me in my hospital bed – moving my legs, working my muscles. In a short amount of time, I was able to get out of bed. With lots of support, I could walk to the bathroom.

Doctors told me that the medical term for what happened to me is “transient quadriplegia.” It’s a bizarre injury. It basically means, “temporary paralysis.” When I was hit, my head whipped forward, causing my spinal cord to stretch and shut off every bit of feeling throughout my body.

After moving from the ICU to the Critical Care Unit to a regular hospital room, I was finally released from the hospital. Three of the longest days of my life ended when I walked out of the hospital with some major assistance from my mom and dad. To be released, I still had to wear a neck brace and use a motorized scooter.

Classes were scheduled to start in about a week and a half. Between my release and school starting, my days consisted of lying on my bed watching TV. I got tired easily and had very little strength.

My mind, however, could not rest. I was still trying to process all that had happened. What in the world was next for me? To be honest, the thought of playing football again didn’t venture into my head as often as I thought it would. I was more concerned about walking on my own.

Even as I was working through what had happened to me, I knew I had to see my teammates before they traveled to Louisiana for the first game of the 2014 season. About a week after I left the hospital, with a lot of help from one of my teammates, I was driven to the brick wall by the football practice fields. I grabbed my crutches and began a very slow walk – or foot drag, as I called it – onto the field to see my teammates practice.

Coach Dave Clawson whistled practice to a stop, and all of my coaches and teammates gathered around me. I spoke to them for a few minutes; I told them how proud I was of them and how I would be watching every play that Saturday against University of Louisiana at Monroe.

I was in my dorm room, and my teammates were in Louisiana. As I stared at the TV, analyzing the plays and cheering for my team, I couldn’t help but notice something. I kept looking at my teammates and realized that they all had the number 45 written on their arms. From the punter to our offensive linemen to our defensive players – every player that I saw on TV had my number written on them.

Oh, it killed me that I was unable to be with my teammates as they embarked on a new season with a new coaching staff. But I could see that I was in fact with them, and it meant the world to me.

While my feeling had returned, my strength had not. In order to regain my strength, I started physical therapy. My therapist, Niles Fleet, and my trainer, Nick Richey, began with baseline tests, and that first session made me realize how much work I had to do. Both men were going to push me harder than I ever thought I would be pushed.

I was like an infant. I literally remember having to practice rolling over on the floor. Every movement seemed so foreign. It was as if my brain and body had no idea how to work my muscles. I had to completely reteach my muscles the simplest of movements – like moving your arms and knowing how to transfer your weight when walking on an uneven surface. Relearning the basic movements of walking was incredibly frustrating.

One of the toughest parts of physical therapy was water therapy. I started most of my session in the water moving and floating around. After being in the water for a little while, I started to feel normal again. I was able to move much easier and I felt strong. But getting out of the water and facing the reality of my injury – that I was weak and was still learning how to walk – was so incredibly hard.

Niles was a really good physical therapist. While others were asking how I was feeling and if I was going to play again, Niles never asked. He greeted me with a smile at every session, and we would just work for hours. His constant presence and supportive attitude gave me strength – physically, emotionally and spiritually – to achieve the goals we had set forth.

When physical therapy sessions started, so did classes. While it might have been wise to take a leave of absence for that semester, I didn’t. No aspect of my life was the same after the hit, and I needed something that hadn’t changed. I felt that continuing my academic pursuits was a good idea.

I was outfitted with a walking cane and a scooter as my transportation around campus. I would ride my scooter from my on-campus residence hall to right outside the classroom. From there, I would grab my cane and inch my way to the closest seat possible. By the time I got to class and found my seat, all of my energy was gone. It is only by the help of my phenomenal professors that I was able to complete all of my classes that semester.

After classes ended each day, I would scoot over to physical therapy for three to four hours. Then, I would ride my scooter over to the Miller Center balcony and watch as much football practice as possible. In the beginning, I lacked the strength to do all of this, but each day I made a little more progress.

Watching my teammates from the balcony was emotional. I still wasn’t sure if I would ever play again. But at the same time, it was fulfilling. These were my brothers. We had worked so hard together; I just had to be there for them every day – even if it was at a distance.

Coach Clawson would talk with me while I sat on my perch. He would toss me a Gatorade and ask how things were going. My teammates would see me and wave from the practice field. I wasn’t physically on the field with them, but boy, I was still with them, and I wasn’t going anywhere.

For the first half of the season, I was unable to travel with the team. Every single weekend, my now-fiancé, Katey Brooks, or my parents traveled to Winston-Salem. My parents would stock my refrigerator and provide support. While I was still wearing a neck brace and depleted of strength, Katey would literally shave my face for me and help me put clothes on. She always did it with a smile.

It was clear that my current life goals had drastically changed. Not many 20-year-olds are learning how to walk again; not many 245-pound tight ends are being carried up the stairs of a restaurant by their friends; not many former athletes lose their balance and fall to the floor in their dorm room, unable to get up.

For weeks, I had worked through hours of intense physical therapy. I wrote down my goals: walk without a cane; get through the day without having to take a nap; focus in class; walk up stairs without holding the railing; play mini-golf. I also recorded “The Good of Today,” every day. What had gone well? What were the victories that day? It helped me see progress when it was so easy to be engulfed in frustration.

One of the big goals for my 21st birthday was to jog. With many of my teammates watching, Niles Fleet, Nick Richey and tight end coach Adam Scheier were at my side as we jogged a lap around the Kentner Stadium track to celebrate my official entrance into adulthood.

Goals continued to drive my work and progress. After going to classes like a typical college student and spending two to three hours a day, six days a week in physical therapy, I thought I could achieve the next one on my list.

On Thursday night, when Wake Forest hosted Clemson, I opened the gate and led my team onto the field. As I ran ahead of my teammates that night, I could barely feel my legs underneath me. I had to focus so that I wouldn’t misstep and fall. But I did it, with the support of my team and to the cheers of the crowd.

I remember it was a Sunday, and I had finally made my decision.

Up to this point, I had debated and wrestled with whether I would return to the football field. I considered the risks involved, and doctors, my parents, friends and loved ones all voiced their thoughts. But it was up to me, and that led to many sleepless nights.

Ultimately, I asked myself one question: If I did play again, would I be willing to take the risk of going through ALL of this over again?

I couldn’t say yes to that. And so, I made the decision not to put the pads on again.

Coach Clawson, Coach Scheier and the entire coaching staff were unbelievably supportive of my decision. After I told them, Coach Clawson looked at me and said, “Whatever role you want to have on this team, you can have.”

That offer was incredible.

I have the aspiration to coach high school football one day, and Coach Clawson offered me an opportunity to be a student-coach during my senior season. I could assist Coach Scheier with the tight ends and give plays through hand signals on the offensive side of the ball. Wake Forest made a way for me to remain on scholarship, complete my time as a member of the football team and get coaching experience.

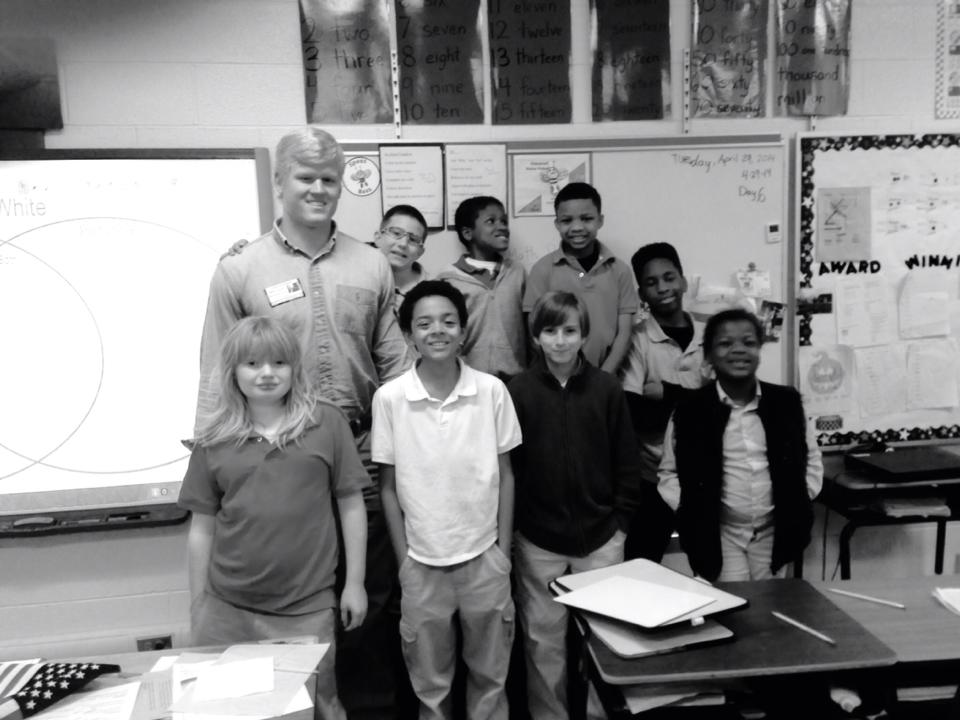

Since the day I started at Wake Forest, I knew I wanted to teach. During the fall semester of my senior year, I was completing my student teaching at Meadowlark Elementary School in Winston-Salem. I had a wonderful class of fifth-graders who were always eager to learn, and always loved talking about anything regarding Wake Forest.

Most days, I would wake up around 4:30 a.m. to exercise and make sure my lesson plans were complete. I would then get dressed – Tuesdays were Bow-Tie Tuesdays, and I always had to make sure I impressed my students with my attire – and arrive at the school at 7:00 a.m. to get ready for the day.

The students began arriving at school between 7:50-8:00 a.m., and from there it was nonstop. I taught all day until around 2:30 p.m., when I would leave school to get ready for practice. I would rush over to the football facilities and get ready for afternoon meetings before practice. Practice lasted until around 6:30 p.m., followed by team dinner. Before I knew it, it was 8:00 p.m., and time to grade some papers. Then, I went to bed so I could wake up and do it all again the next day. It was a busy fall semester, but one I will never forget.

As President Hatch was delivering his opening remarks at graduation, my mom noticed a butterfly on her program – a symbol, in my family, of God being near.

I am a firm believer that God places events and experiences into our lives for specific reasons, even if at the time we may have no idea what that reason is, and even in the time following, we still may not know that reason. These moments that God places in our lives often times fill us with happiness, peace and joy, and often times they fill us with confusion, sadness, frustration, and even doubt.

Through this experience, I was shown just how beautiful the smallest things in life are. From moving my big toe, to walking without a cane, to walking in a straight line, to eventually running and being able to jog a lap around a track on my 21st birthday, I have learned that those tiny moments in life are what are most important and beautiful.

I have also learned that all we are given is the present moment with those we love and those around us. Yesterday is dead and tomorrow hasn’t arrived yet; we have but one moment with the ones we love, and it is our duty to seize those moments, to take hold of the happiness and peace within those moments and to cherish them and put them into our hearts forever.

Although my journey at Wake Forest was completely different than how I envisioned it, it will forever remain one of the greatest journeys in my life. From the faculty, to my friends and teammates, every individual I came across was such a blessing. To my entire Wake Forest family, I say thank you.

Throughout this entire journey, my trainer at the time, Nick Richey, gave me some of the greatest advice I have ever received. As I continued to struggle with not playing and my future not involving playing football, he told me that all we can do is hope. It did not make sense why my injury happened. It did not make sense how I was given the opportunity to walk again. It did not make sense that one plus one did not equal two, and he was glad it didn’t. He told me that all we can do is hope that one day it all will make sense, and each day, live in that hope with a smile on our face. Live in the hope that no matter what someone is going through, one day it will all make sense.

As I walked across the stage at Commencement, it began to make more sense. As I shared memories with all of my family who was in town for graduation weekend, the reason became more clear. As I proposed to my now-fiancé this summer, the fog of my injury began to clear. Is the specific reason for its occurrence crystal clear? No, and I am not sure that it ever will be. What I do know is that I was given the opportunity few people who suffer this type of injury are given, and I will forever seize that opportunity.